Pain of Pleasure

Text by Domenico de Chirico

In Western thought, pleasure has always been conceived as a positive, compensatory, at times domesticated experience — one capable of offering a brief reprieve from the sense of emptiness. Yet each time pleasure asserts itself, it also reveals its own negation.

There is no pleasure without risk, excess, exposure, or dislocation — nor without the shadow of a wound. Georges Bataille, in fact, described pleasure as a transgression of being: an outward impulse, a rupture of the boundaries that enclose the subject within its seemingly stable form, the moment when the naked self separates from the ego cogito.

Thus, in its most extreme dimension of freedom, pleasure becomes an experience of the beyond — a threshold where the individual encounters both their own essence and their own dissolution.

Conversely, if for Bataille pleasure is impulse and excess, for Roland Barthes — as suggested in A Lover’s Discourse: Fragments — it turns into its own shadow: a language of absence.

Here, every act of love shatters the self; it asserts and dissolves it at once, leaving image to the imaginary, as though one loved love itself more than the beloved. Pleasure thus appears as a paradox: a vital force that carries within it the shadow of death, a form of knowledge that emerges only in the moment it is consumed.

The exhibition Pain of Pleasure arises precisely from this structural ambiguity.

Its title evokes a short circuit between two apparently opposite yet co-essential experiences: ecstasy and suffering, surrender and resistance, love and violence.

Following the logic of jouissance — the Lacanian notion of enjoyment that exceeds the pleasure principle, an excessive, often painful satisfaction beyond mere gratification — the exhibition explores what happens when desire ceases to be symbolic and becomes corporeal, material, and unassimilable.

Desire emerges as an impersonal, incandescent energy capable of traversing bodies and transforming them into fields of high intensity.

Yet every intensity entails a fall, the point at which energy is exhausted and converted into loss.

It is in this ongoing exchange between power and ruin, between Eros and Thanatos, that Pain of Pleasure finds its inner rhythm.

The works of Christa Joo Hyun D’Angelo, Mads Hyldgaard Nielsen, and Sally von Rosen inhabit this dialectic: desire as both transgressive force and as aesthetic and political principle.

Their works do not simply depict pleasure or pain — they embody them as states of tension, offering alternative, tangible modes of knowledge within an increasingly complex reality.

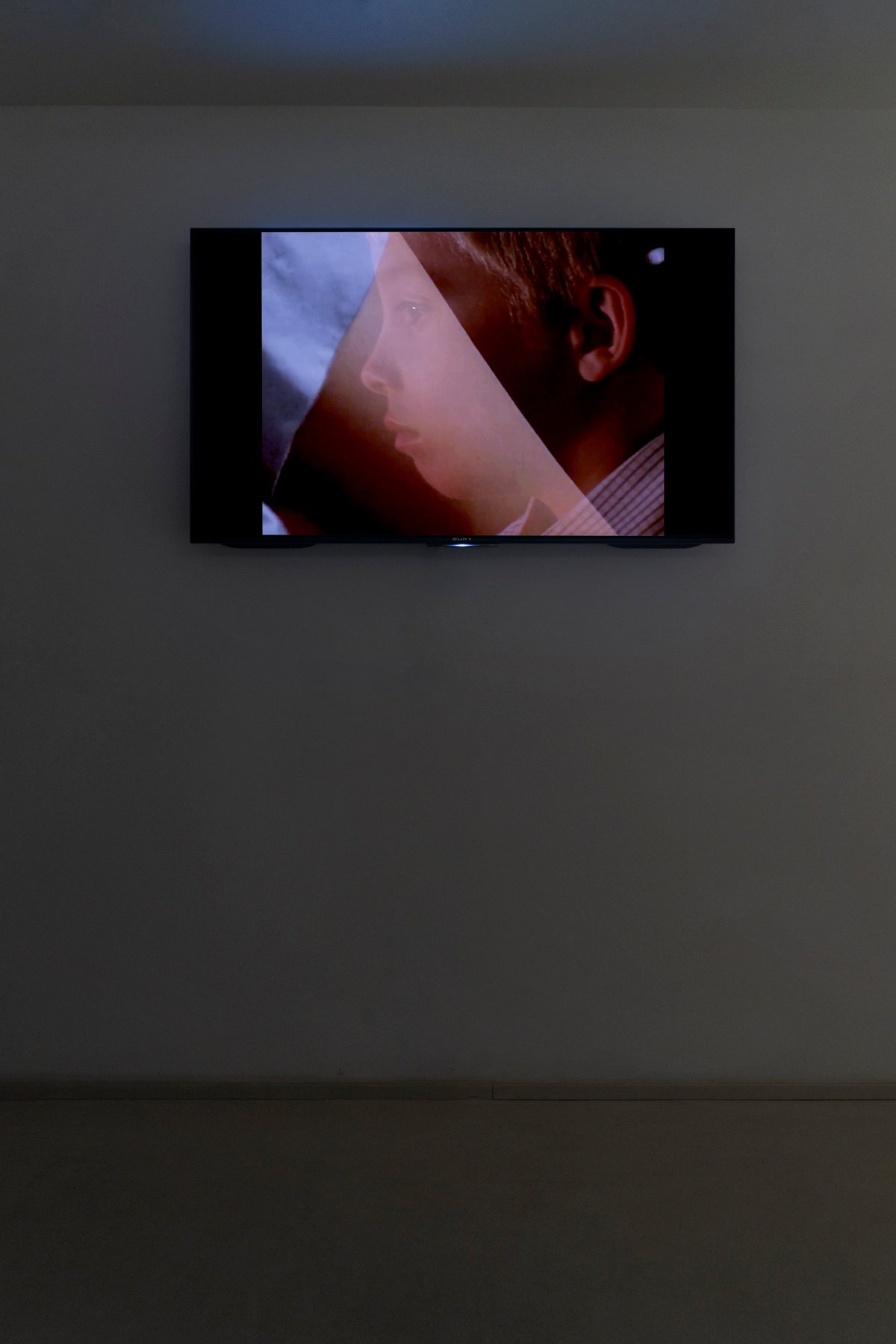

In the video The Death Drive – A Love Story, Christa Joo Hyun D’Angelo investigates the topology of trauma and the drift of love as a form of domination.

The title itself — invoking Freud’s death drive — situates the work within a logic of destructive repetition, where desire tends more toward annihilation than life.

Through a construction that intertwines cinema, pop culture, and testimony — alternating black-and-white and saturated color, sound, dialogue, and monologue — D’Angelo composes a psychic montage, a stratified narrative that probes familial trauma and its inevitable intergenerational transmission.

Drawing inspiration from Rosetta by Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne, suspended between childhood and motherhood, as well as from Asia Argento’s The Heart Is Deceitful Above All Things and Gianni Amelio’s The Stolen Children — all marked by abuse and disquiet — the work unfolds as a parable of contemporary society.

This genealogy also includes the case of brothers Erik and Lyle Menendez, who murdered their parents after years of sexual, physical, and emotional abuse.

Here, love becomes both language and weapon: a site of distorted desire and inevitable punishment.

Meanwhile, the neon piece PLAY WITH ME — a pop quotation and distinctly perverse mantra — exposes the ambiguity of a mediated eroticism that confuses seduction and submission, power and vulnerability.

D’Angelo’s work ultimately does not represent violence but stages it as an affective grammar that roots itself tentacularly in love, feeding on its very wound.

Forged from the light and shadow of the past, with a seventeenth-century breath, Mads Hyldgaard Nielsen’s painting takes shape as a quest for the sublime through matter.

His works, composed with symphonic structure, act as musical movements — inner tempos of tension and release.

Clouds of smoke, explosions, and flares, amid golden surfaces and incandescent magma, emerge as phenomena of energy and disintegration, evoking a pictorial language that does not describe but occurs.

In this performative dimension — recalling Gilles Deleuze’s Logic of Sensation focused on Francis Bacon — the body, at times human, at times statuary, never objectified, becomes vibration and field of opposing forces, fulfilling a “logic of sensation.”

In particular, in the painting VI MVMNT Finale, the contorted, luminous figure embodies the threshold between ecstasy and pain, vital impulse and surrender — a silent cry, a lyrical-erotic tension that does not resolve but persists in the dense, tenebristic matter of color.

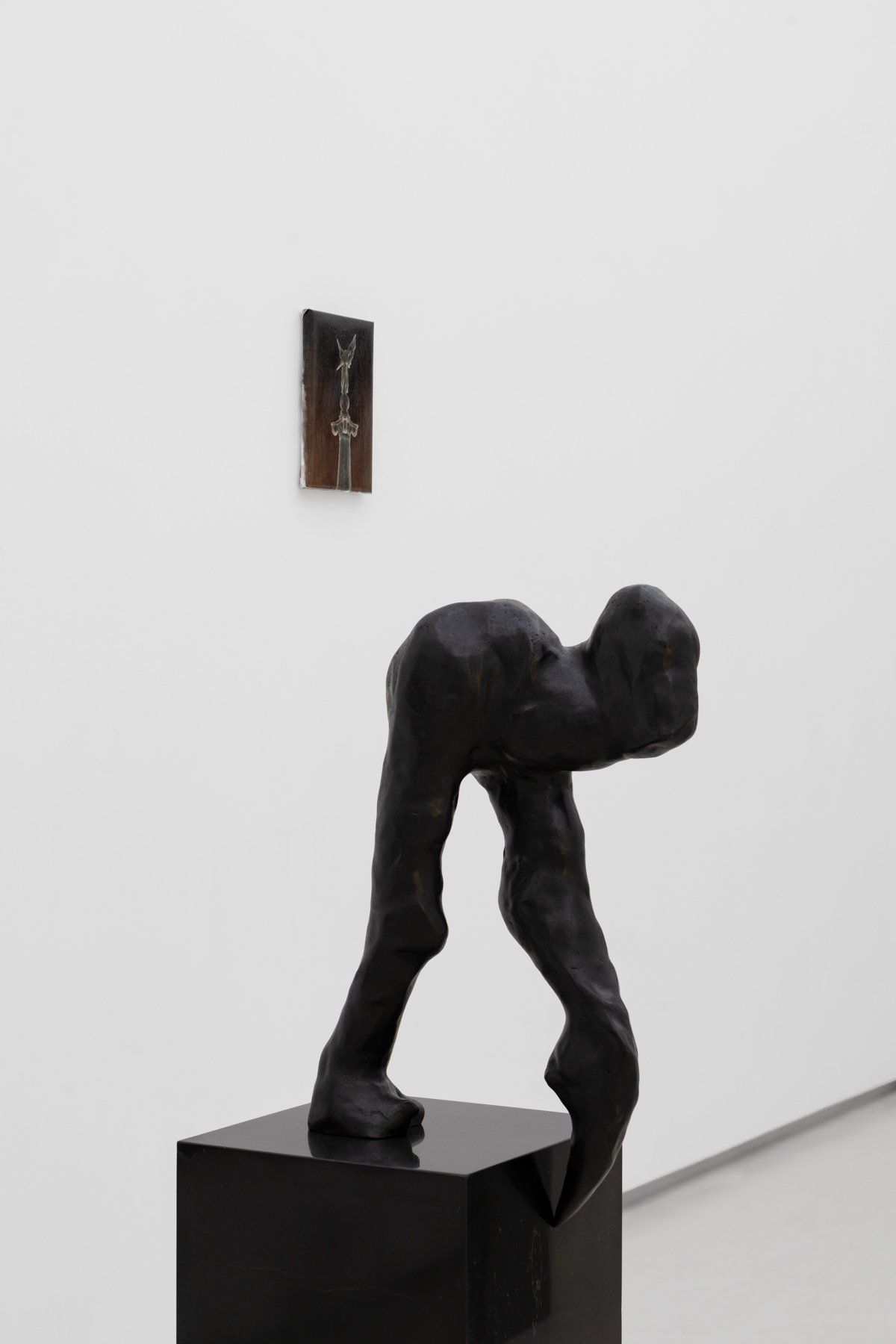

Sally von Rosen’s two sculptures, Tristo and Rosemary, radicalize this perspective, pushing desire onto the terrain of living matter.

Hybrid and metamorphic forms — simultaneously organic and artificial, archaic and post-human — reveal an interest in the intrinsic vitality of matter, aligned with Jane Bennett’s theory of vital materialism, which posits that all entities, human and non-human alike, including inorganic matter, consist of “vibrant matter.”

In these works, the body admits no closure, revealing itself in continuous becoming.

Anatomical fragmentation and erotic tension place von Rosen’s sculptures within a lineage that connects Hans Bellmer’s corporeal surrealism and Lacan’s psychoanalytic notion of the corps morcelé — a fragmented, incomplete subjectivity perceived as dismembered rather than coherent.

Here, the body becomes a site of division and desire, an organism in constant redefinition.

Von Rosen also reclaims and transforms the ritual and performative dimension of 1970s feminism, restoring to the body — and to its matter — a direct political power made of fragility, exposure, and metamorphosis.

Within this heterogeneous weave of rigorous, lyrical, and fearless poetics, Pain of Pleasure takes shape as a reflection on desire as a form of knowledge that passes through the body and its crisis.

Though moving across distinct registers — narrative, pictorial, sculptural — the three artists share a desire to explore the threshold where identity dislocates, consciousness yields to matter, and matter becomes language.

They stage a body that exposes itself in order to recognize itself, that wounds itself to feel alive, while confronting the horror that sometimes inhabits human experience.

Beneath the spotlight of a stage marked by affective anesthesia and the growing virtualization of bodies — between emotional detachment and possession, saturation and alexithymia — Pain of Pleasure offers a radical reflection on sensitivity as a form of resistance.

Pleasure and pain, in their interdependence, become practices of knowledge and presence: experiences that restore to art its original function, embodying within the sensible the indissoluble unity between aesthetic value and vital impulse.

As Jean-Luc Nancy reminds us, “Being is always being-with”: being in contact, in the wound, in the shared vibration of the world.

Therefore, Pain of Pleasure offers no catharsis but a liminal experience.

It does not invite a choice between pain and pleasure but to dwell in their co-belonging, in that point where one transforms into the other.

There — where the skin burns and living, conscious matter breathes — art returns to what it has always been: an act of existence, fragile, piercing, and fully alive.

Thus, in an age when pleasure is often reduced to consumption and pain to spectacle, the works of Christa Joo Hyun D’Angelo, Mads Hyldgaard Nielsen, and Sally von Rosen restore their original dimension: extreme, vital experiences that return to sensitivity its complexity, its darkness, and its depth.