DREAMS:WORK

or Working dreams, dreamy work, dreams of work

“Night, suicide of the eye” – Unknown author

“That’s what the world is, after all: A never-ending battle of contrasting memories” – Haruki Murakami

You always miss the moment when you fall asleep. You literally sleep through it. It’s a logical problem—because even if you consciously work toward that moment (by using breathing techniques or counting sheep, for example), falling asleep itself is something you can’t consciously perceive. That is in its nature—because it is precisely the other side of consciousness that you are looking for—and which is sometimes difficult to reach.

How this other side takes shape can vary greatly. Sometimes it is more fantastical, sometimes more exciting or romantic. In any case, normative standards of space and time are suspended. How this happens is decided by that other side itself, the reverse side of consciousness, as it is always shaped by the desires, fears, and narratives of this side. The other side dwells within us, yet we have little access to it. We need it, the beyond, in order to be able to endure this side, to “process” it, as they say.

Nevertheless, the hereafter needs the here and now at least as much as vice versa. Every front has a back—and every back has a front. The stories that seem fantastic are generated from the already grotesque reality, but in reality, they only depict the truth in an exaggerated (or softened) form. The darker the reality, the brighter and more comforting the “other reality” may be. Rarely, but sometimes, you can still perceive fragments of how your own perception dissolves, distorts, and twists as you fall asleep. Sometimes, words you just thought, images, figures, and objects mix together. Objects grow wings, people grow four arms, houses grow upward and downward at lightning speed, up and down. You still waver, because you know you could perhaps still tame it, the fantastic reality you are now exposed to could take two of the people’s four arms away again, making them recognizable individuals, just as the houses shrink back to their normal size. Then comes the moment when there is no turning back. Then you know that it is happening. That you are finally stepping over to the other side of consciousness.

The group exhibition DREAMSWORK is located precisely in that liminal space between sleep and waking—and thus sheds light both on unimagined possibilities and on the impossibilities that limit us in everyday life. The state of half-sleep is also a political space, which means a space in which the otherwise unthinkable suddenly becomes visible and imaginable.

Almost like in a lucid dream, in which you can control yourself in a half-awake, half-asleep state of consciousness, various levels open up here, entire worlds that remain invisible during the day. Unknown territory is revealed and explored—a technique that becomes ingrained in the dreaming body and can be repeated by it, becoming reality because it has already been practised in the dream. A dream—whether a daydream, a half-asleep dream, or deep in the REM phase—is a place that shows that more is possible than what is commonly believed to be possible. It teaches you to see—and sometimes it enchants your surroundings a little, making you aware of how much the life you lead and the way you look at it can be shaped by yourself. The shift in dream worlds sharpens the senses for the shifts and absurdities that are always present in everyday life when you cast your eye on them. A collective potential that can not only depict the world, but also shape it.

Each of the positions we encounter in DREAMSWORK has a different approach to this very shift, which we encounter not only in dreams, but which we usually overlook when awake: In the title of Camillo Paravicini’s painting alone, we encounter a use of words that only at second glance reveals that they subtly subvert familiar idioms: “A doctor a day keeps the apple away.” Liminal poetry. Landscapes, grimaces, and figures repeatedly emerge from his surreal-looking paintings, only to disappear again just as quickly as they appeared. As with a picture puzzle, viewers see primarily what they want to see—each viewer gives what they see a specific meaning based on their own constitution and experience, which, like a dream, can evaporate at any moment. It lingers like a synesthetic memory on the tongue, which can still be tasted but is difficult to grasp in words. Lizzy Ellbrück’s work makes the corner of the room the object of observation—the corner that can only ever be viewed from one side, and around which one can therefore never walk. Does the corner also have a back side? And why is it always that corner where the daily house dust lands, most of which, as we know, consists of skin particles from the inhabitants of that house? She herself describes it this way: “It is where the unconscious lingers. It is the edge of a space, the limit of perception – yet, within its confines, entire worlds may unfold.”

Like in a dream, I think.

Sara Gassmann’s vessels, which are both paintings and objects, also exist between formation and deformation. A vessel is shaped by its contents just as much as the contents are shaped by the vessel. The vases also function here as an archive that preserves thoughts, impressions, and experiences. Carrier or memories.

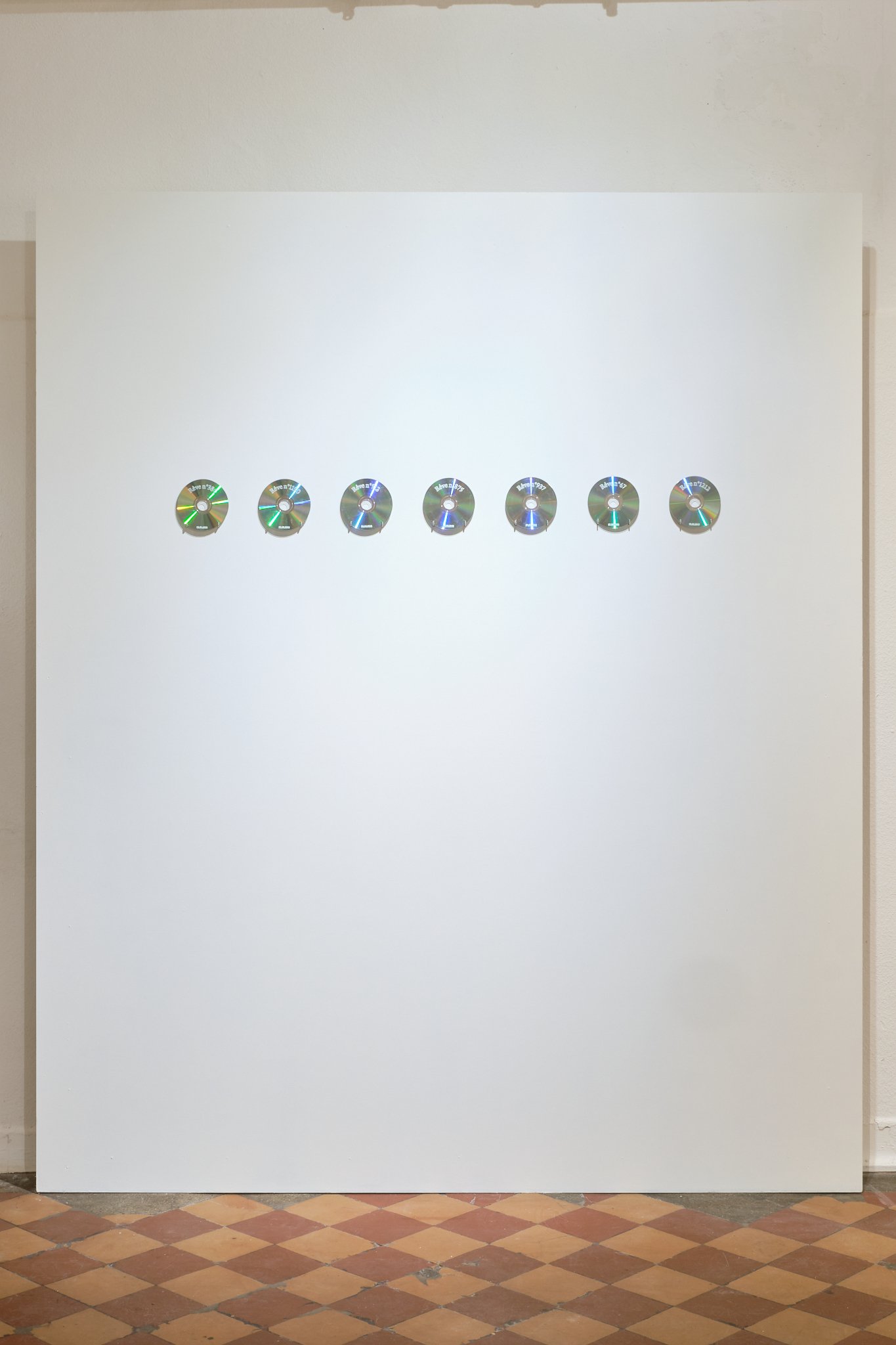

Rose Le Goff’s work also deals with archiving the ephemeral—she records her dreams on a storage medium with an unclear expiration date. The human brain functions like such a storage —in order for the past to have space in it, something has to be thrown away, forgotten, from time to time. A workshop where thoughts work—or dreams. But the storage medium itself, the CD, is also something nostalgic. And it too has a limit to the amount of data it can hold, just like the human brain. It is still said that hardly anything is as likely to remain in the memory as the spoken word: oral history remains the most reliable way of transmitting information.

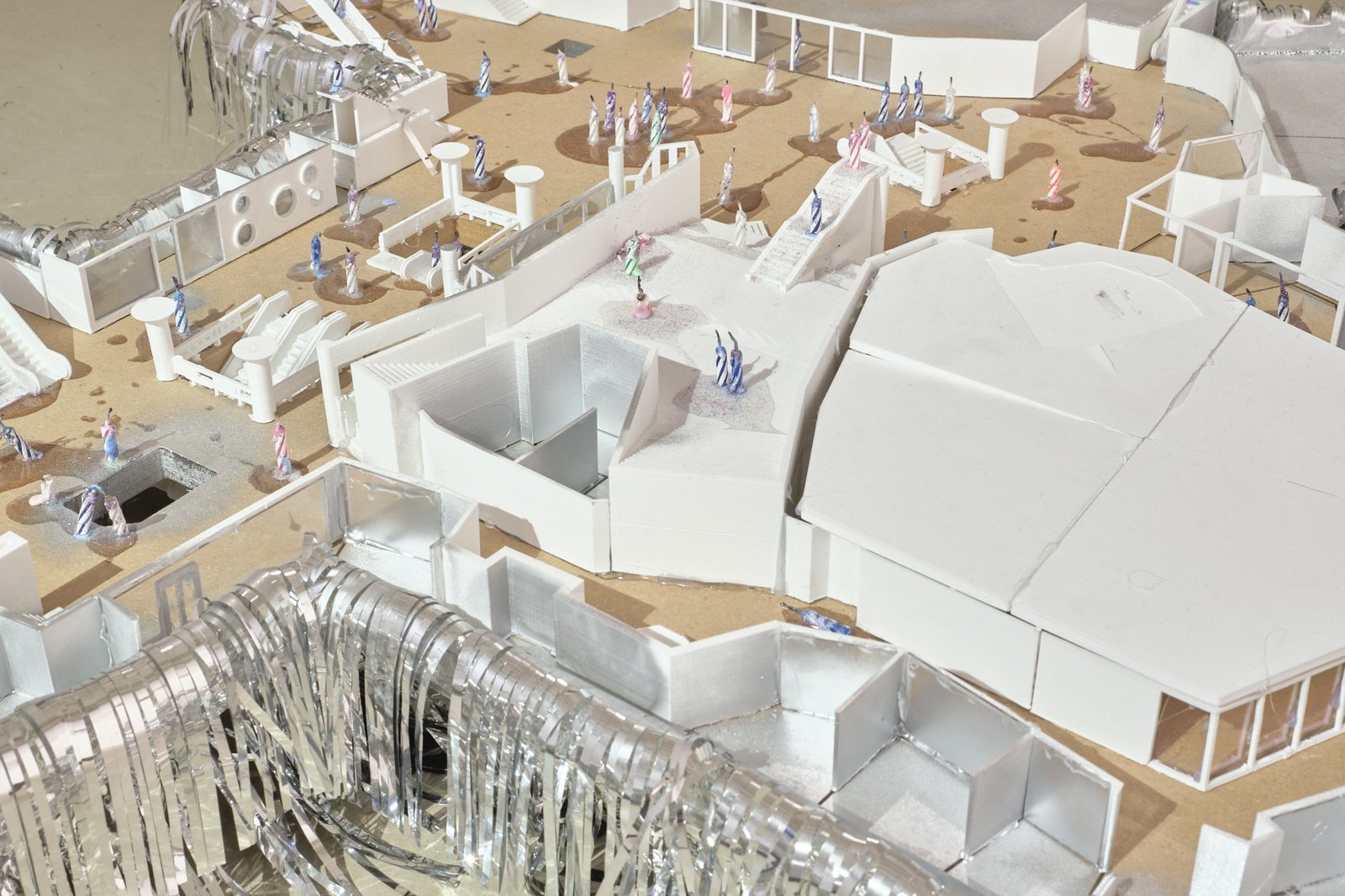

Time and again, it is the everyday places of encounter and objects of everyday life that, in their shifted appearance, suddenly take on something uncanny: in Cyril Tyrone Hübscher’s model of a Frankfurt subway station, the protagonists are represented by candles (as on a cake), which, once lit, have a certain finiteness inherent in them. The bird’s-eye view that one is forced to adopt when “looking down” on the model is reminiscent of how one sometimes perceives oneself in dreams, from above. At the same time, however, it is also reminiscent of those hobby models of train stations that can be found in larger stations—and whose trains can be set in motion by inserting coins. An anachronistic toy.

Rafael Jörger’s work, a wardrobe installed on its side, looks like something that has been left behind and not yet picked up. It, too, is a container. A creaking and groaning container —perhaps it is just woodworms, but perhaps it is also haunted by the ghosts of past owners. “Home is where the haunt is,” writes Mark Fisher—and every piece of inherited furniture is charged with hauntings. What is really hidden inside it—objects, a person, a portal to another world—is unknown. It introduces a space for thought that is locked behind the closed cabinet door. Perhaps it conceals the possibility of a new order. And in its mundane impenetrability, it always plays with the viewer’s desire—as in Lacan’s theory of the “objet petit a,” the desired remains unattainable anyway, the door never opens more than a crack. And perhaps it is not meant to, because the desire for revelation remains in limbo. Even in this quality, the mundane object has an inherent sense of the “uncanny.” The concept of the “uncanny” combines the secretive with the familiar. The ghostly, the strange, and the terrifying often hide in the all-too-familiar, in everyday scenes. Suddenly, you find yourself a guest in your own house, or the protagonist in your own nightmare; horror occurs in familiar sheets. Sometimes the abyss can even be found within one’s own body, enclosed by the skin in which we live—people are their own worst enemies. Everyday life becomes the scene of the terrifying, the grotesque—one can neither look away nor look directly at it.

The work of Alexandre-Takuya Kato has a similarly eerie feel to it—it is a window in which, in a doubling familiar to us from those very dream realities, another window opens. An almost “Alice in Wonderland”-like shift: from the dream itself emerges another, unpredictable dream world. Spontaneously, one thinks of the narrative principle of the movie “Inception.”

In Noémie Vidonne’s work, too, the layers merge—this time not so much layers of space as layers of time. She blends elements of a childhood in the early 2000s, which occasionally remain as reminiscences in school notebooks, wallpaper, furniture, or in cupboards, with the folkloric inlay technique of her home region. I am thinking of the principle of intergenerational timekeeping—time levels are layered vertically on top of each other instead of horizontally, chronologically, side by side, as is usually the case.

“When authors write about dreams, I immediately stop reading,” says my friend A., and I agree with him: fiction within fiction is one level of fantasy too many—you lose the ability to believe the omniscient narrator. But which narrator can you believe anyway, who is “omniscient” about their own life – in this world or the next?

Aren’t we all just the unreliable narrators of our own life stories?

And I think of something I once learned: you can’t die in a dream. Because before that happens, you always wake up—that’s the nature of dreams. If you die in a dream, you have also died in reality. “Reality”—that means the other reality.

“In my dreams, I’m always in a flight mode,” says M. Sometimes even on a white horse. For me, it’s always the action of falling that recurs. Falling out of a window, for example. Before I hit the ground, I wake up, of course. Waking up means changing reality. Leaving the paralysis of sleep behind. Finding yourself back on the “other side,” which in reality may be no less distorted, warped, exaggerated, or grotesque than the world of dreams. Every perception, whether asleep or awake, is already distorted anyway—shaped by the organ with which we perceive, by the state we are in, by light and air quality. The dream is a doubling of the non-dream, the dark twin sister of the day. “How your night is, is a result of your day,” I learn. And sometimes life at night is brighter than during the day. And thus shows us everything possible, even outside of night, if only we allow ourselves to look closely. How much more malleable things are when we allow them the potential for malleability—like in a lucid dream that we control on the one hand and surrender to on the other. Somewhere between control and relinquishing control. Because we may need more space for the unexpected, for surprises, than we believe. And it is closer than we think.

Text: Olga Hohmann