“Palmo panorama” — what a strange title. That was my first thought when Marco Emmanuele showed me the draft of the invitation to the opening of his solo exhibition at the LABS gallery. And yet, on closer reflection, the two words placed side by side manage to express and hold together the various tensions within the show: the contained scale of a palm and the vastness of a panorama; the infinitesimal and the monumental; all the way to — with a small mental leap — the friction between the confined space of the studio and the potentially boundless expanse of the landscape.

It’s a play of dualities that also emerges in ISO #250: a work of ambitious scale — practically the size of a soccer goal — yet one whose power lies in a multitude of tiny particles, in an aggregation of glittering elements. Who knows how many grains of sand and glass fragments this piece contains — probably the centerpiece of Palmo panorama, if only for its size. The first time I saw it in the artist’s studio, I had to take a few steps back to take it all in with my eyes, and then photograph it with my phone. It’s striking to think that such a vast surface is made up of microscopic parts, only seemingly the result of broad brushstrokes. Anyone familiar with Marco Emmanuele’s practice knows well that his artistic process is based on a technique closer to mosaic; or rather, a peculiar meeting point between painting and mosaic, between the laying down of color and the juxtaposition of small elements. The artist doesn’t use brushes, but a spatula with which he spreads this mixture of glass and sand onto the canvas — like a mason engaged in something other than the construction of a building, devoted more to poetry than to architecture.

The result is astonishing: the crushed glass from old bottles, mixed with sand, comes back to life in the form of an abstract landscape. A landscape in which the elements — earth, air, water, or something closely resembling them — seem to vie for space, intertwining in a swirling motion. It almost feels like witnessing the act of creation by some timeless divinity (“an unknown and chaotic god,” to quote a line from a poem by Valentino Zeichen, dear to the artist). I’m not sure whether Emmanuele’s works possess a true point of view, an orientation, or specific coordinates; however, I like to think he intends to suggest a vertical gaze, as if ISO #250 were a territory seen from above. Despite this hypothetical distance, the crust of this Pangea is easy to perceive: a rough yet precious “skin” that — thanks also to the large scale of the canvases — embraces the viewer standing before it. In this way, the gallery acquires a horizon that breaks through the white walls of the space: in this sense, I’m fascinated by the idea that ISO #250 can be read as a vast window onto an imaginary landscape.

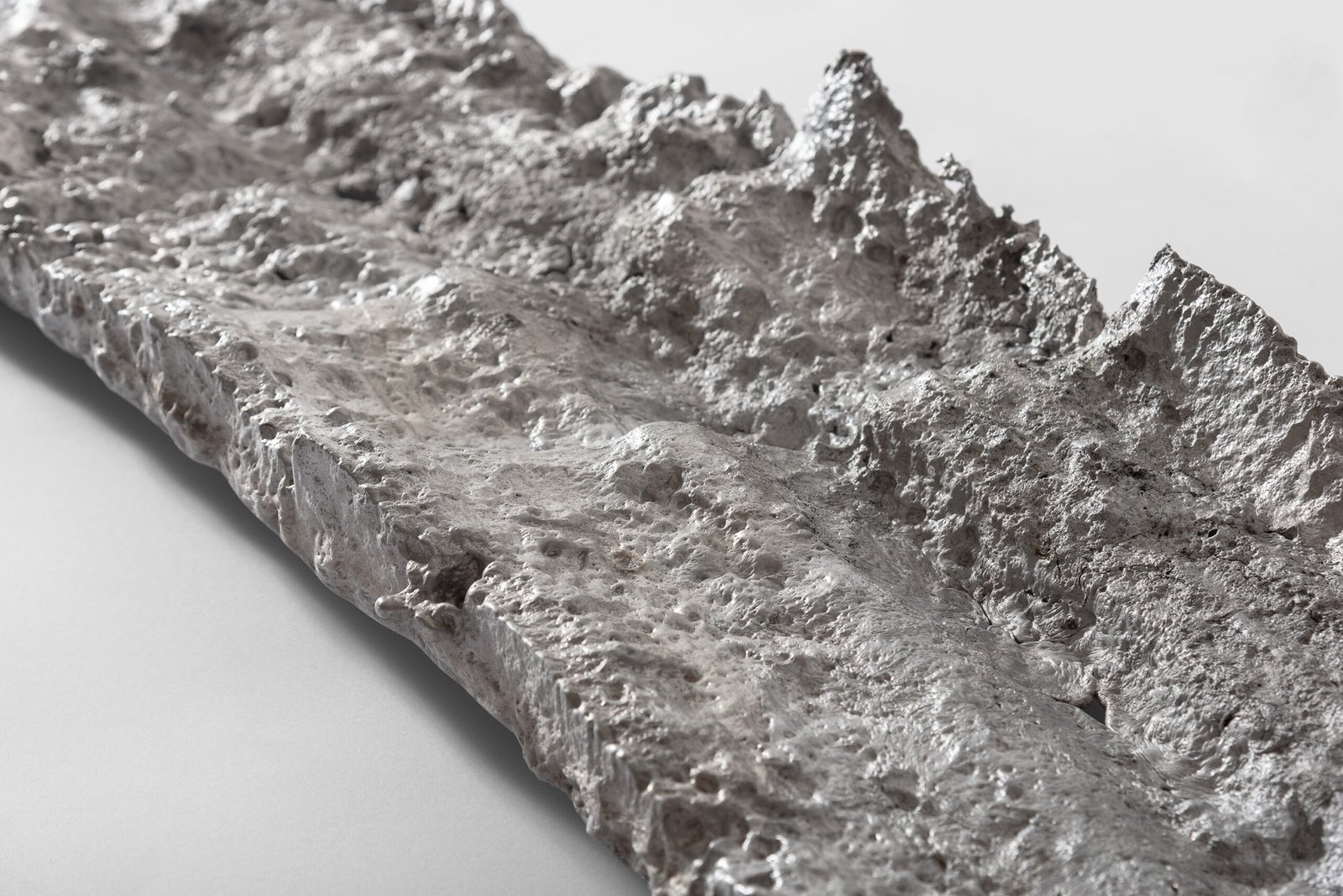

To this panorama, another is added — one even more earthy and three-dimensional. The gallery floor is dotted with a series of five works resembling clods of soil. This is a new direction for Marco Emmanuele, who created aluminum castings of portions of sand furrowed by what appears to be a hand (and in this sense, the title seems to invite yet another interpretation: could the palmo be that very hand sinking into the sand?). The gesture of the hand — and therefore of the body — slicing through the sand evokes an idea of exchange between landscape and action: it is a human movement that shapes the panorama, that renders it — in some way — form. Emmanuele crystallizes that piece of sand through a classic act of material transfiguration (in this case, something soft or malleable made solid), yet he adds another layer: to carve the sand, the artist wielded iron plates cut with a laser according to the profile of five poets’ faces. Dario Bellezza, Giorgio Caproni, Jolanda Insana, Lucio Piccolo, Valentino Zeichen — it is the silhouettes of their faces that trace those grooves, in a gesture meant to honor these writers by linking them to something carnal and earthly, much like the language of their poetry.

Looking at these works, one can’t help but think again of a small demiurge at play — a child on the beach sculpting a marble track. This is the strongest image evoked by the Ruscente series, suggested precisely by the presence of several glass marbles that — like a discreet base — support the aluminum castings. The marbles allow the sculptures to lift slightly from the ground, creating a minimal yet striking sense of suspension. This gentle levitation is one of the precious details with which Emmanuele has chosen to punctuate the exhibition. Palmo panorama certainly owes much to the large scale of its centerpiece, ISO #250, yet its subtler notes shouldn’t be overlooked: the marbles themselves, for instance, or the small drawing of two hands just barely touching — both underscoring, I believe, the importance of gesture in the artist’s practice, the weight he assigns to the act of making. The drawing is displayed in a secluded spot, almost as if it needs to be sought out — much like Occhio di bimbo viperino, which likely reveals itself to most visitors only at the end of their visit. The piece is a bronze cast of a walnut shell, like an orbit containing within it an eyeball represented — once again — by a small glass marble. At the beginning, I described ISO #250 as the queen of the exhibition; yet I find that this little eye possesses a surprising power, akin to that of a “ghost track” you don’t expect at the end of a music album, or an amulet found by chance on a beach in autumn. I’m amused by the thought of this work as the peephole through which that unknown and chaotic god watches, like a good voyeur, the very exhibition he himself has created.

Saverio Verini