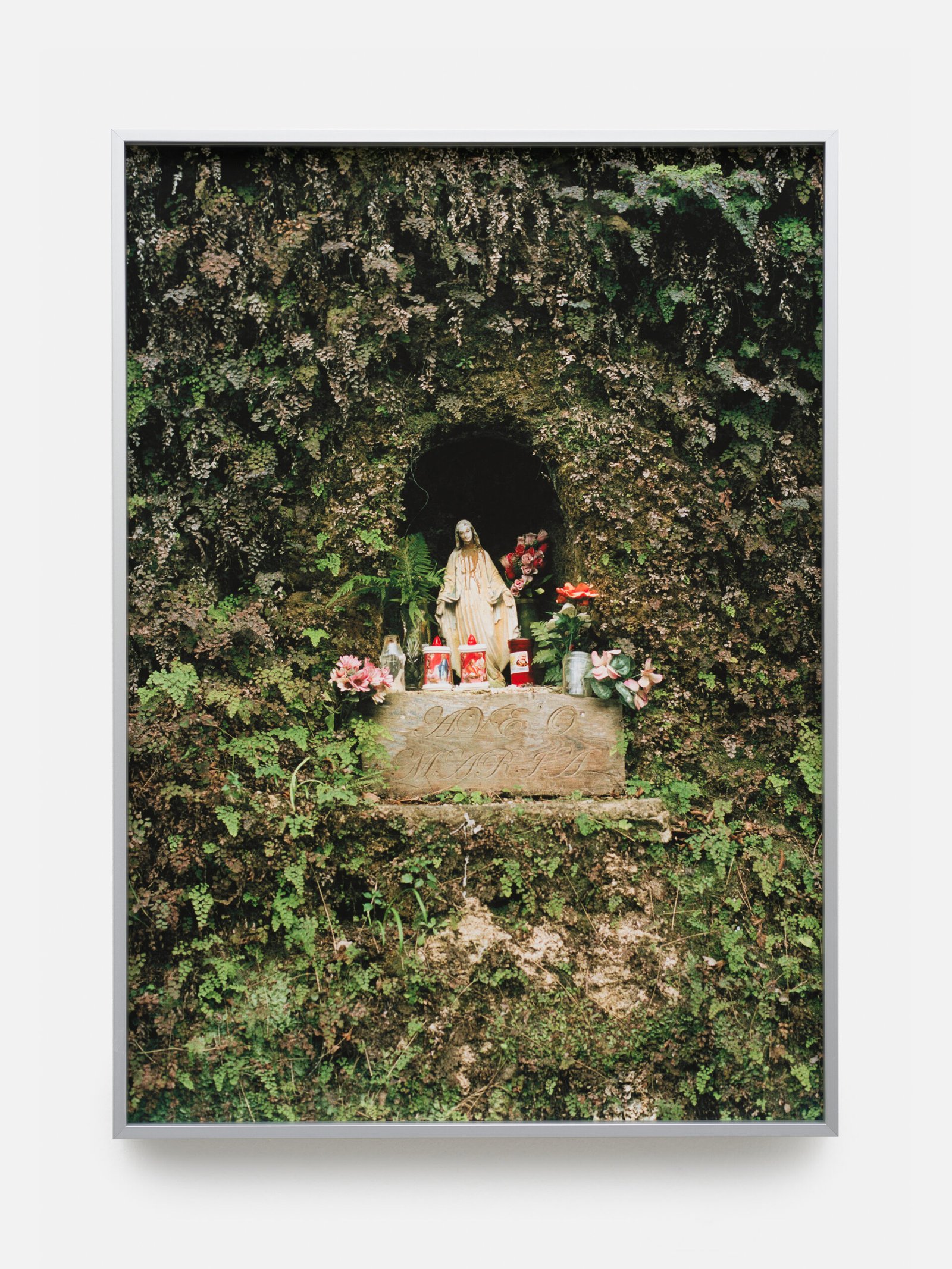

Talisa Lallai’s landscapes evoke specific places, but more powerfully, they conjure the feeling of a longed-for, personal elsewhere. The narrow mountain roads depicted in “Fiamma 2000” (2025) present shades of viridian green, earthy asphalt grey, and unreal blue skies, which appear in saturated, faux vintage images that may recall long journeys taken as children to a Southern European setting. Travelling from a larger city, or even another country, with outmoded hit songs like “Si può dare di più” playing, singing along on repeat in an attempt to forget the absence of air conditioning in the old, compact Fiat Uno. Is that final peak in the image, the one furthest back, perhaps Monte Sellaro on the Calabrian horizon?

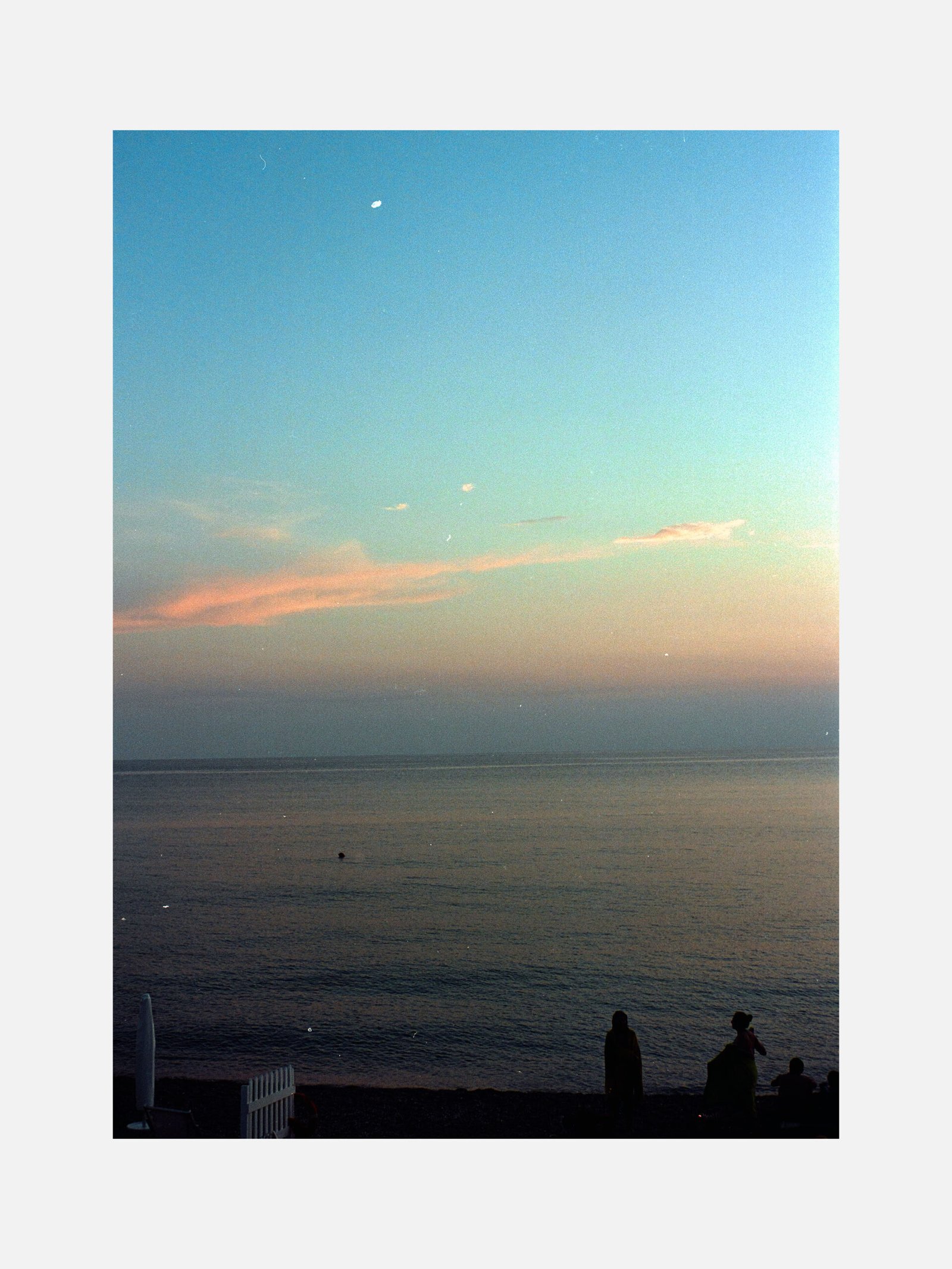

The periwinkle sunset light over the still ocean and its shore come together in “People on Sunday” (2025). The time of day can be inferred from the silhouetted figures at the very bottom of the image, who are darkened by the backlight. These silhouettes are caught mid-motion, gathering their belongings and preparing to leave – an echo, perhaps, of the memories of twenty-something mothers at the lido in high-legged neon swimsuits and Lycra bikinis, shouting at their Antonios, Francescos, or Giovannis as their boys drop their gelatos in the sand after hours spent unsuccessfully chasing tiny fish along the pebbled shore. Their not-quite-aunties soothe them, chatting all the while and lamenting the departure of their own children to capital cities in search of more viable livelihoods than a touristic village could offer.

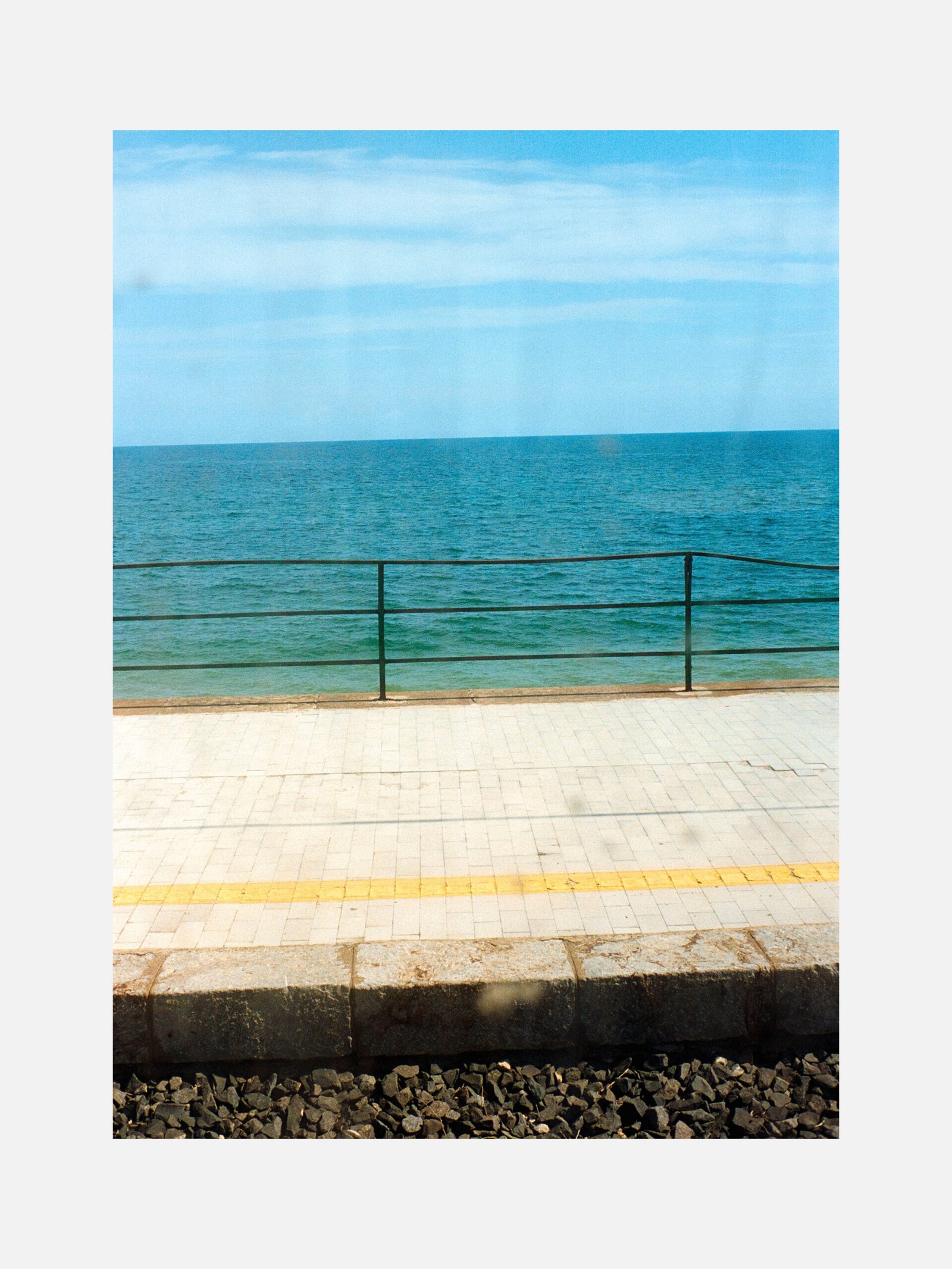

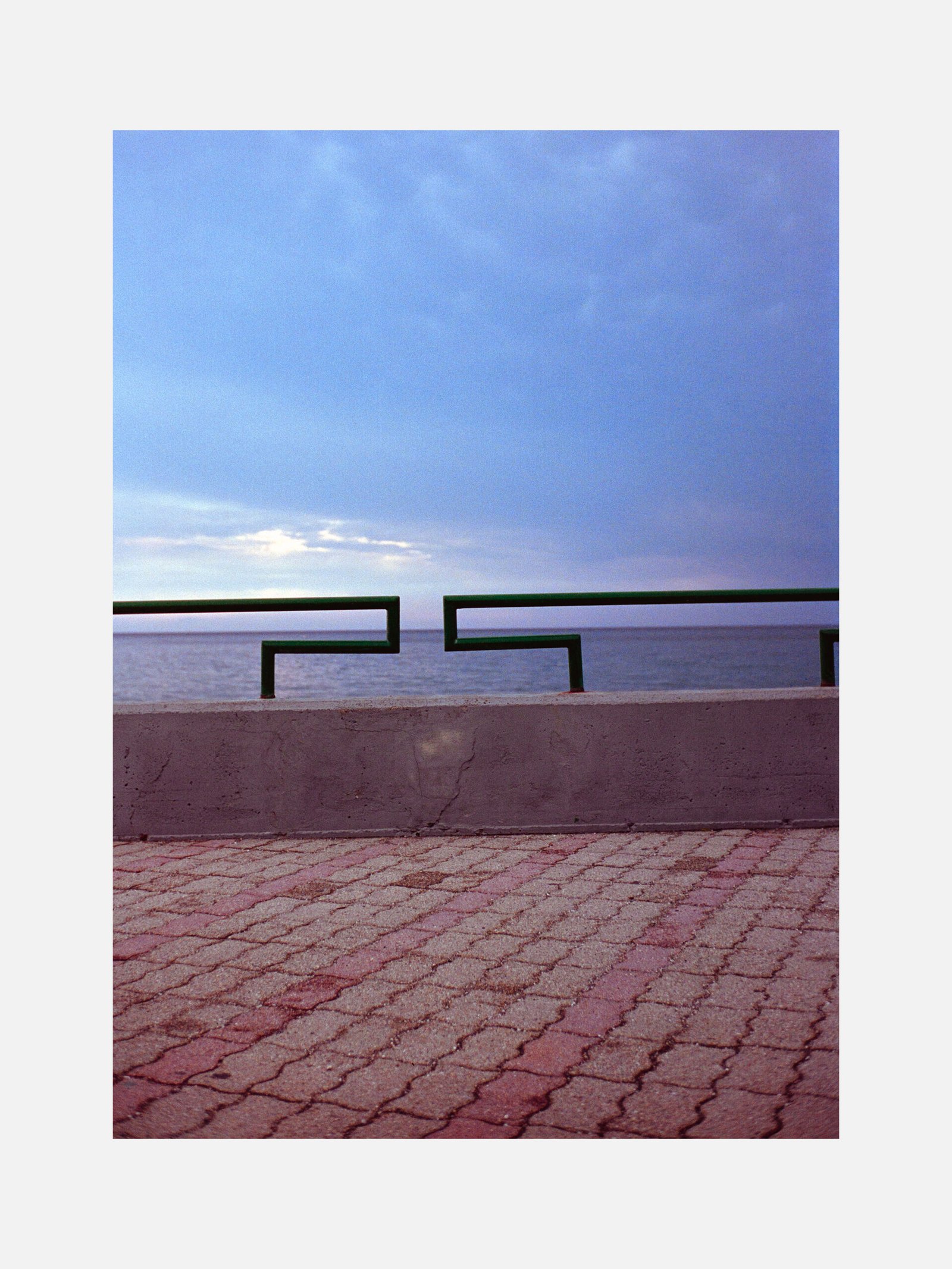

At the end of the day, the mothers would lead their children away from the beach as the little ones fiercely defended the right to play a while longer, sometimes gripping rusted railings with their small, determined hands, and casting dramatic glances back at the ocean. Their forgotten plastic shovels were now left to the sand and eventually submerged by the rising tide. “Growing Pains” (2025) and “Cruel Summer” (2025) capture these feelings with instinctual ease, depicting empty seascapes from the other side of the same rusted railings that mark the beach’s terminus. These compositions – rendered in turquoise, blue, and beige – read almost like colour-field paintings translated into photographic form.

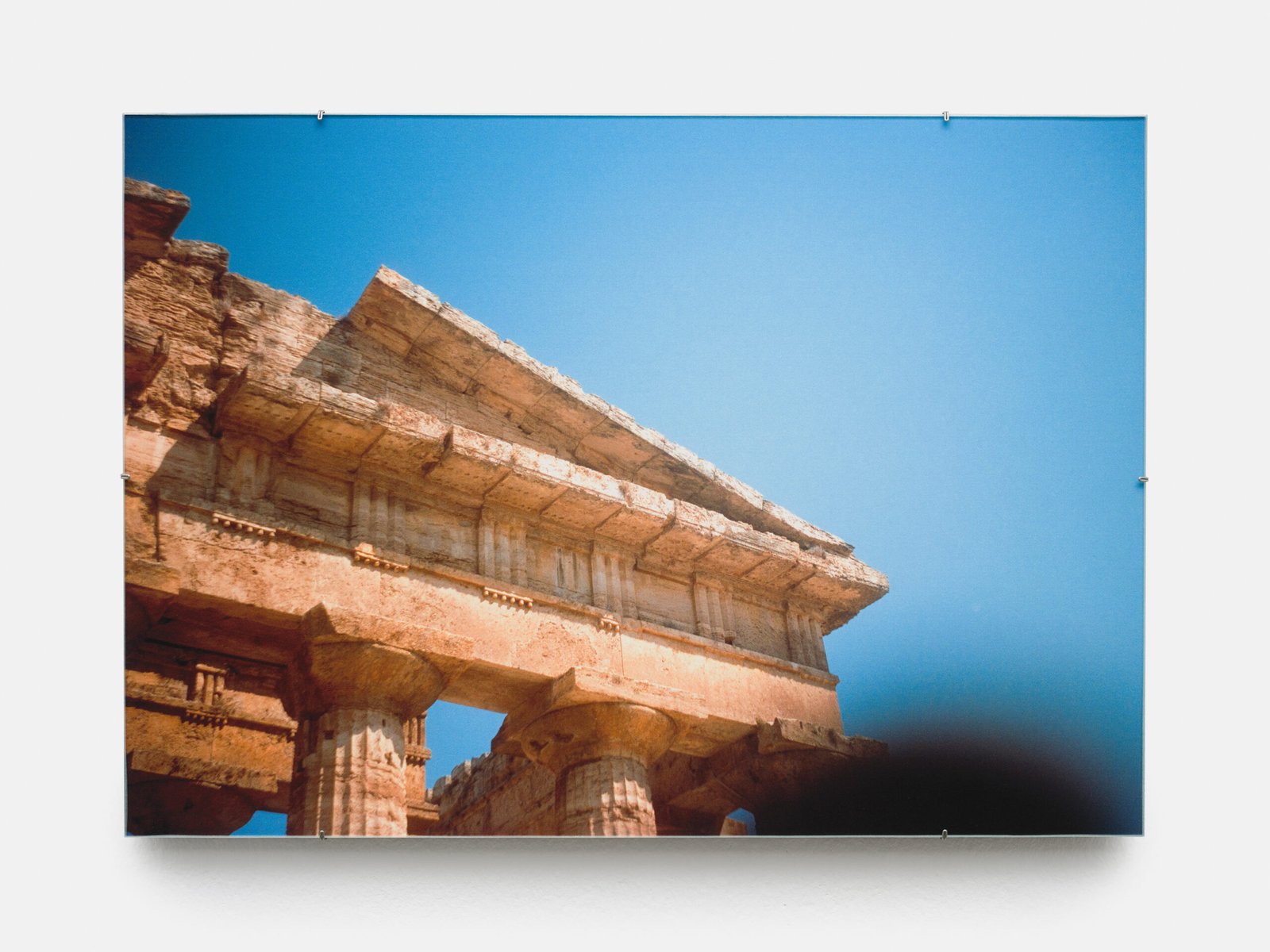

In a similar light, some of Lallai’s photographs depict identifiable locations rendered in fragments. “Hera II” (2025) reveals a corner of a Greek ruin’s entablature set against yet another intense blue sky. A dark intruder appears furtively at the bottom edge, perhaps a finger brushing the lens as the shutter closed. It’s easy to imagine the pre-teen Alessandras, Valentinas, and Federicas lingering near the ruin, role-playing as ancient Greek goddesses and arguing over the temple’s true name. Some parents insist it was built to honour Hera, others swear it belonged to Poseidon. The ruin under question may indeed be the Temple of Hera II, one of the three most ancient Doric temples in Paestum. Despite daily wear from salt crystallisation and seismic micro-fractures, no other entablature in Paestum is better preserved – and few are anywhere else either.

“First Light” (2025) appears as a rather abstract and mysterious depiction of a room in the dark, from which very few elements are recognisable. A vertical yellow stripe appears at the image’s edge, as if the following room – a better illuminated one – lies just out of frame. From the few recognisable elements, one would perhaps think of a Palazzo with its colourful frescos and ornaments hidden in the darkness. The room could be the Sala del Mappamondo (Hall of the World Map) at the Palazzo Farnese with its fabulous depiction of the 1574 version of the world; it is deliberately kept away from view. This obsolete vision of the 16th century’s truths might resemble a future obsolescence of the certainties of today.

Whether by design or chance, Lallai’s images deceive in much the same way memories do; they become fragmented and increasingly fictionalised the more they are summoned. They drift away from the original event, just as Lallai’s photographs stray from their source motifs. Composed of formal accidents and details emerging from anecdotal or oblique angles, they function more as symbols of longing than documentation. “Simple Times” celebrates what is usually discarded and it is an ode to the unreliability of memory itself. Each viewer’s longed-for place can be projected onto the images, allowing them to evoke personal associations beyond any specific location.

Gabriela Acha