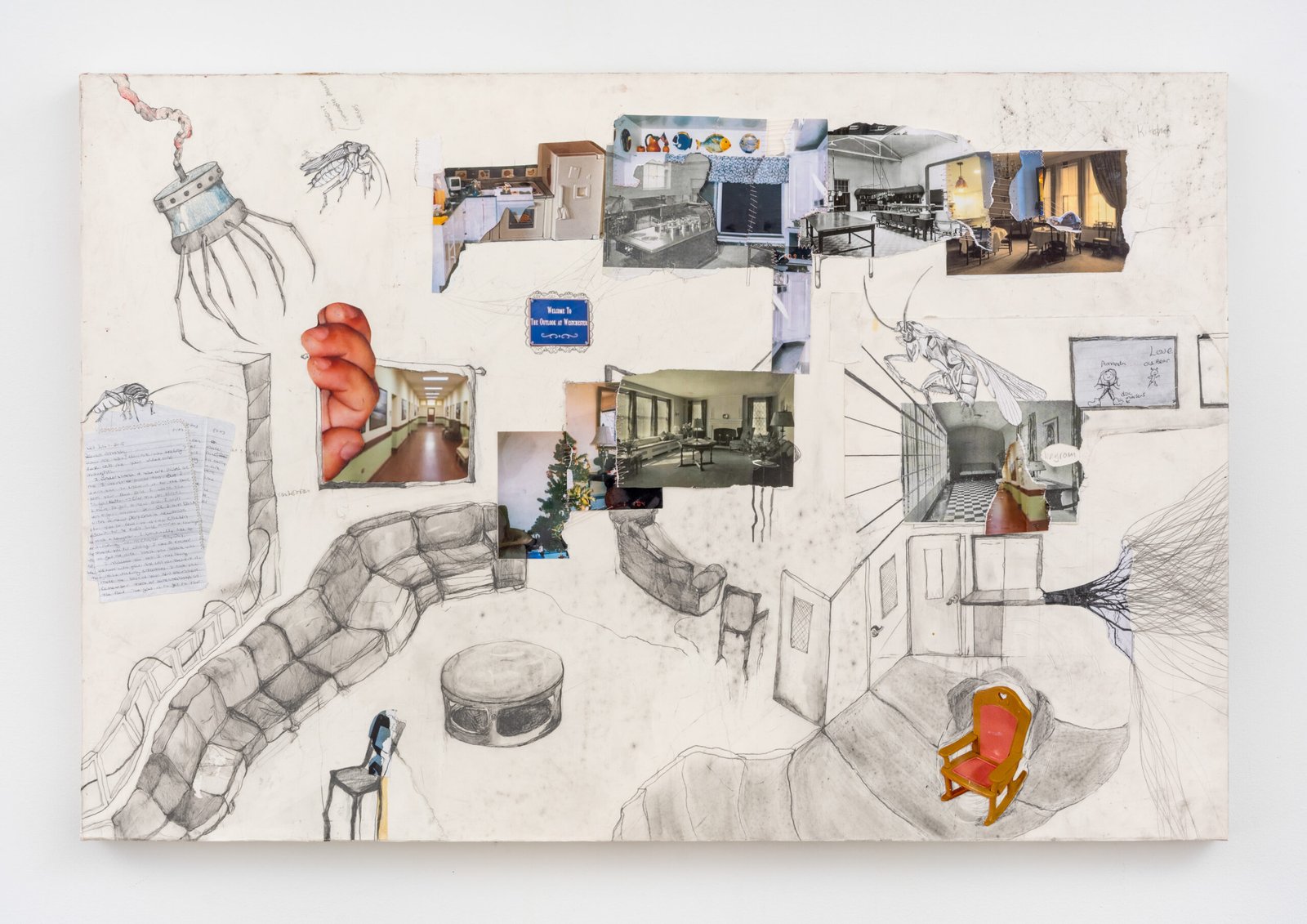

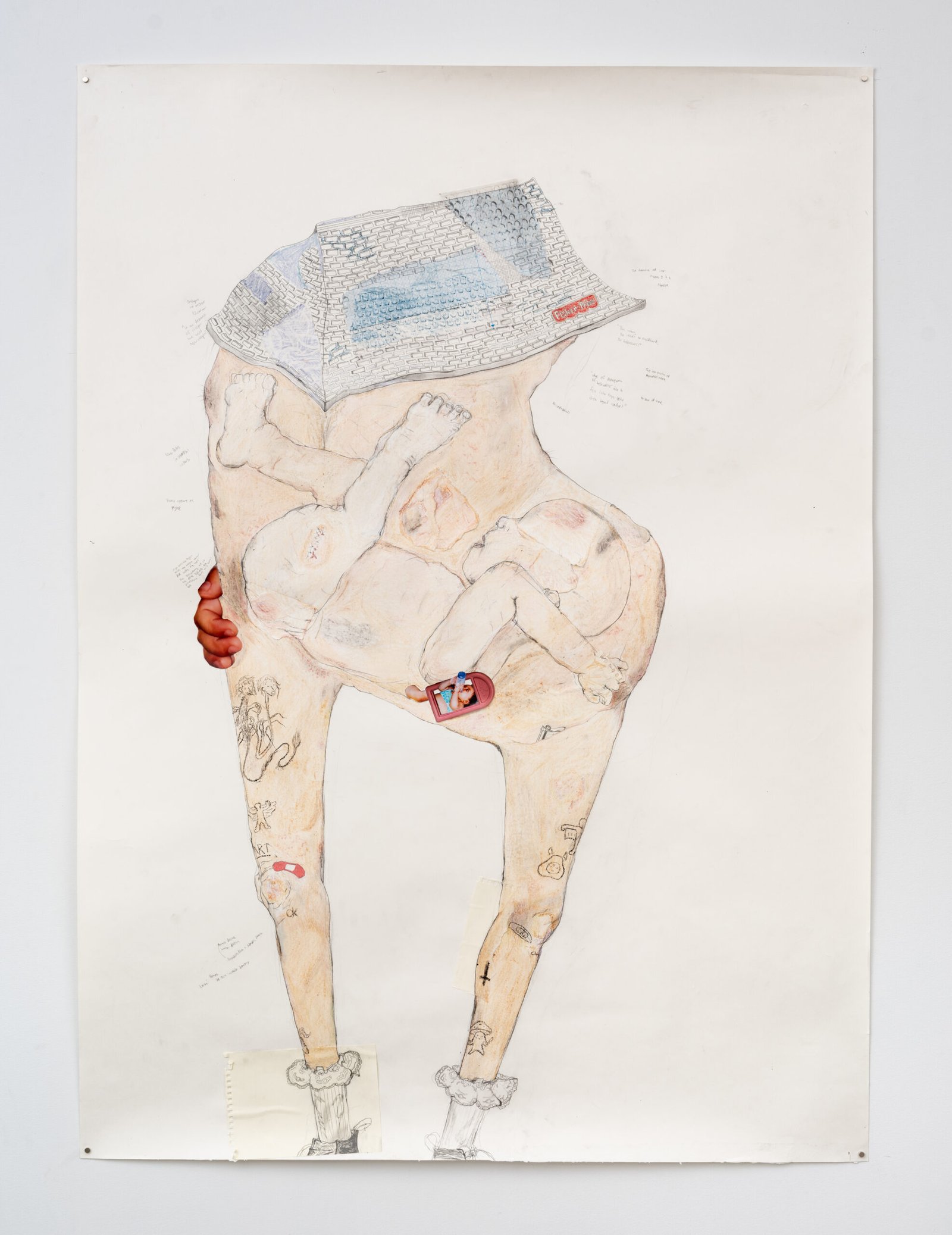

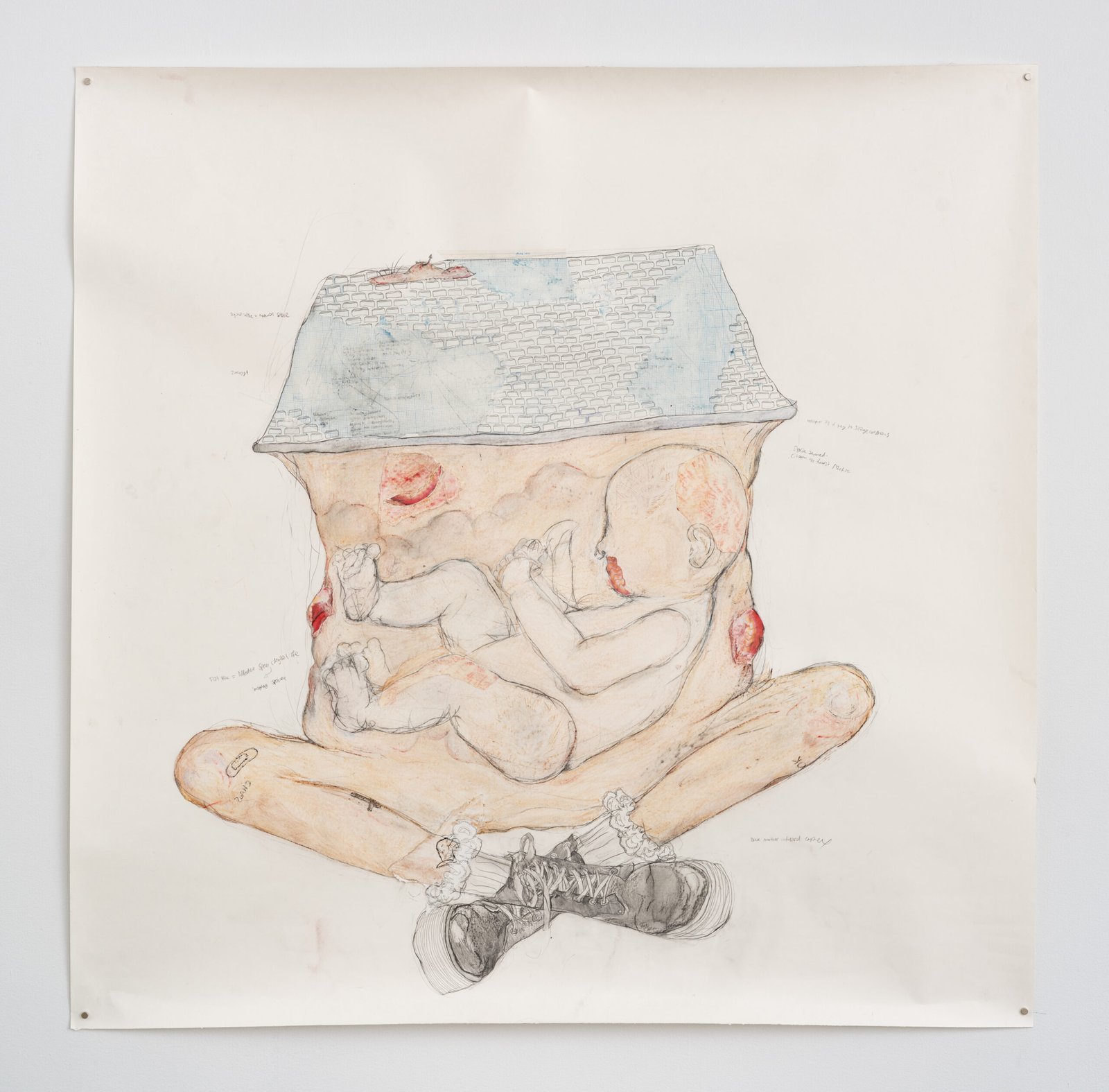

Are there any safe spaces? A childhood home? A hospital? Inside the body? In the womb? In the sticky embrace of a spider’s web? Are we safe inside our memories? Inside imagination? Ophelia Arc takes us to these places. There is serenity there, with soft materials and a palette of subdued fleshy hues. But there is also a disquieting sense of peril. A kitchen iterates unstably, and a living room becomes claustrophobic with reduplicating sectional furniture. A Fisher-Price Dollhouse makes several cameos. It serves as a gestational prison; it appears trapped in a fibrous cage, gets ensnared in a web, and is severed apart only to be precariously re-bound by corset strings. Arc’s spaces are equally sites of repose and discomfort. We are caught in the transfixing dialectic of the beautiful and the abject. This is a world of ciphers, abounding with meaning but impossible to decisively decode.

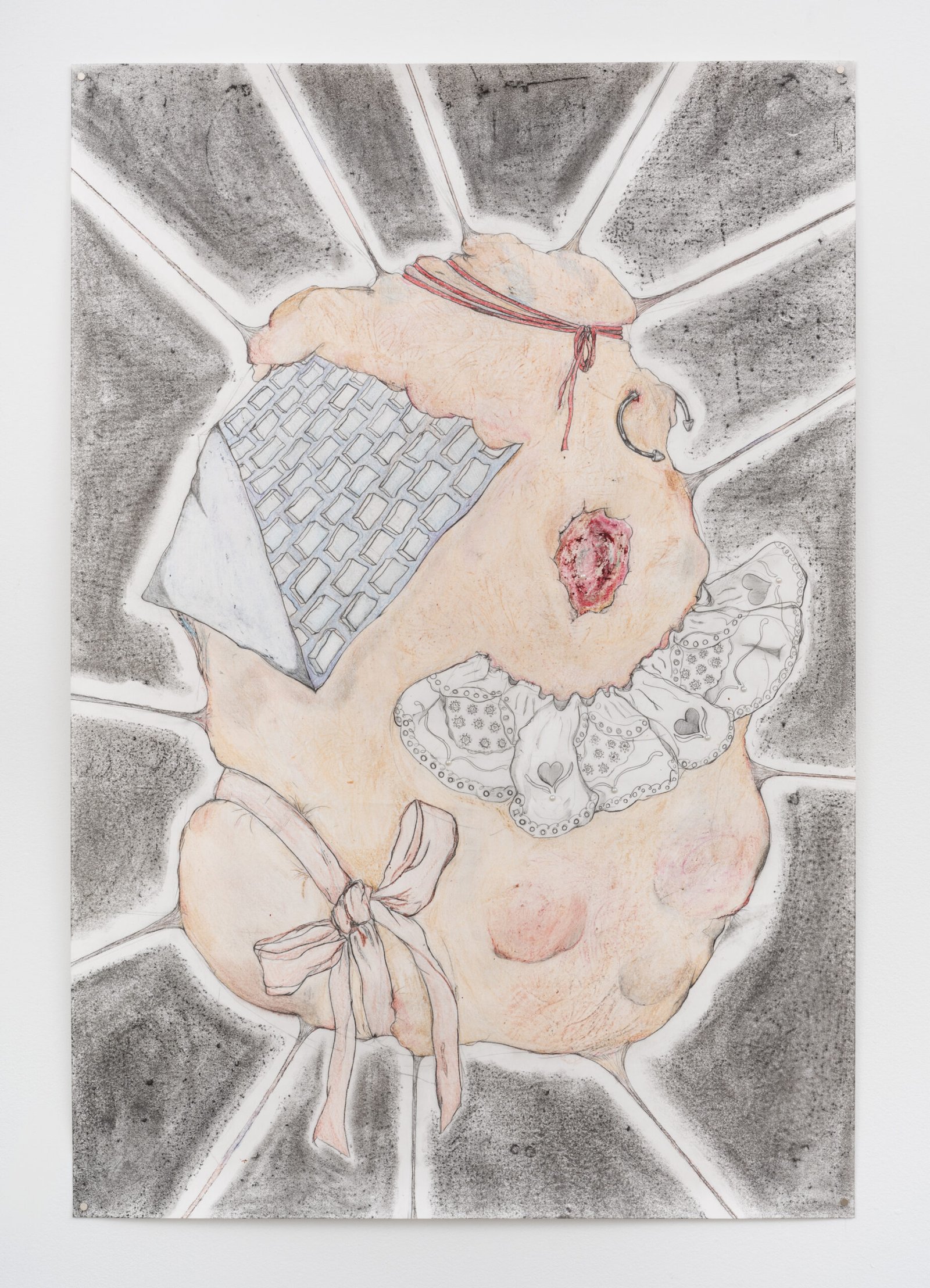

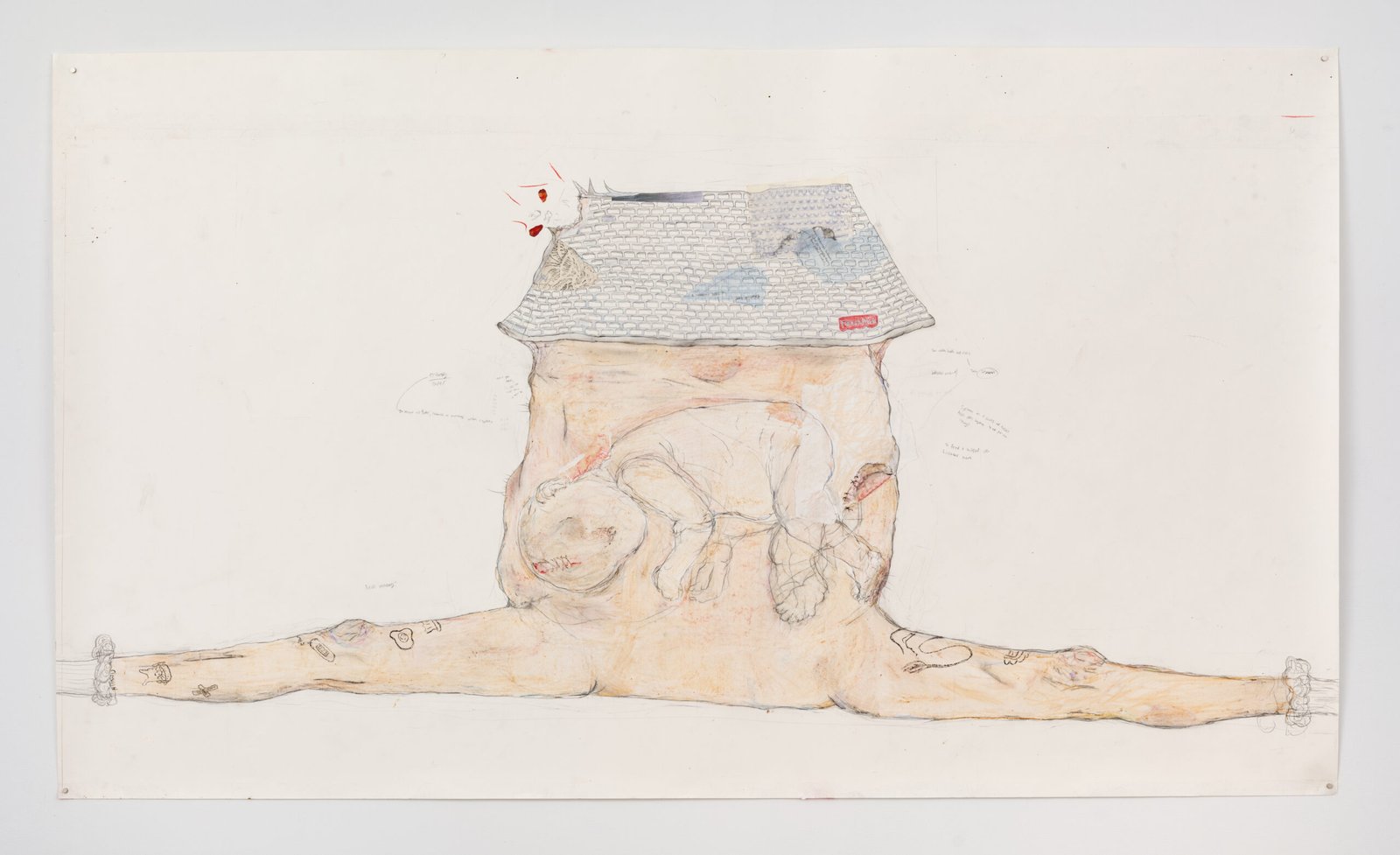

Ophelia Arc’s work confronts us with the fragility of embodiment. This is not the embodiment of dynamic athleticism and agency, it is an embodiment of viscera and flesh. Both dermal and subterranean, excavating the amorphous parts within. The surfaces are scratched and bloodied, marked by tattoos that serve here as the scars of memory. There are sores, sutures, and lesions, and bandages on scarred knees, reflecting the wounds of childhood. We peer into the artist’s mouth and encounter unnamable organs. There are allusions to medical realms that promise little hope of cure. There are umbilical cords that simultaneously nourish and bind.

The materiality of the work is also operative at another level: in the choice of media. In addition to paint, crayon, and archival and personal photos, we find plastic, magnets, coins, refuse of process and plexiglass. Throughout, there is also the persistence of crochet, laboriously stitched with hand-dyed yarn.

Other soft materials include thread, tulle, latex, gauze, and ribbons. The use of fiber introduces a gendered

dimension. Crochet, in particular, is denigrated as a craft medium, as a pastime for grannies, the stuff of sweaters and scarves. Here, it is appropriated to render phantasmagoric medical models, webs, and sutures.

The title of the exhibition, The Natal Lacuna, is drawn from A Natal Lacuna, an essay by the French feminist philosopher Luce Irigaray. In it Irigaray argues that the prevailing symbolic order treats the generic or universal subject as masculine. Against this phallocentric background, women struggle to define themselves. They are given the unattractive options of defining themselves as they appear in the male gaze, or else as lack—femininity becomes a kind of deficiency or absence of masculine traits. To escape these alternatives, Irigaray enjoins women to define themselves by inventing new modes of expression. She describes transgressive acts of self-creation as a kind of birth. The natal lacuna refers to the prevailing condition of absence from which women must self generate.

Ophelia Arc is both delivering on Irigaray’s injunction to create a new language and offering a sly counterargument. Themes of pregnancy connote a birthing process, but the babies look more entombed than enwombed. Oversized, bruised, and inert, nothing portends an impending birth. In A Natal Lacuna, Irigaray offers an ambivalent appraisal of the surrealist author and artist Unica Zürn. Zürn suffered from bouts of physical and mental illness and was hospitalized numerous times before taking her own life at 54. Themes of psychological disintegration pervade her work, and her visual art is disjointed, unsettling, and difficult to parse. For Irigaray, these images fail to fill the natal lacuna, and Zürn’s psychological condition is characterized as an unpromising strategy for escaping the male symbolic order.

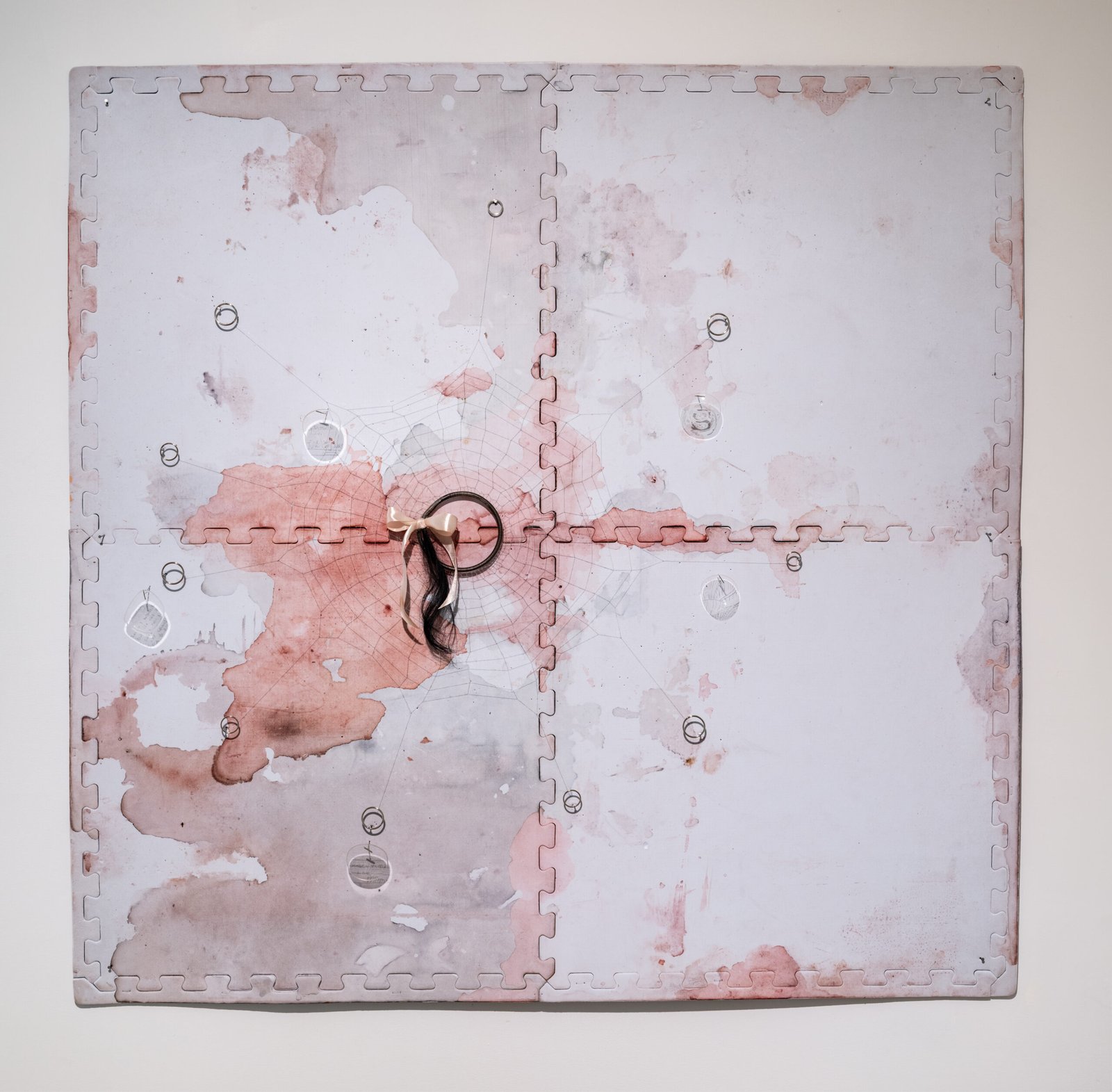

Ophelia Arc’s art subversively counters this critique. Arc pays tribute to Unica Zürn’s stirring books The Trumpets of Jericho, a disturbing fable of childbirth, written after Unica Zurn had her two sons and undergone a self induced abortion and The House of Illnesses, which describes a period in which she was hospitalized for jaundice. Zürn suffered a psychotic break during that stay. She began to associate each ward with different body parts. Some were deemed safe, while others were carefully avoided. Foremost among her safe spaces in the hospital was the cabinet of the solar plexus. The hospital is a recurring theme in Arc’s work, and the solar plexus is the subject of one of her crochet pieces—with a web entrapping a Miraculous Medal (Medal of Our Lady of Graces), a recurring symbol in both the artist’s childhood and her art.

In this body of work, Arc is reclaiming illness as a legitimate site of self-creation. There are palpable signs of fragility everywhere, yet in Arc’s hands they also become an affirming kind of strength. Arc shows that Irigaray is too wedded to binaries like sickness vs. health and ugliness vs. beauty. Arc’s work challenges these, along with the dichotomy between safety and danger. This is epitomized by the spider’s web, a space that is both a home and a trap, a space that both captures and cradles.