I quit drinking a few months ago, because I had more work ahead of me than I could reasonably complete with a hangover. This fairly dramatic change in my diet had two notable consequences: I started eating far too much candy; and the emotion I had been (largely unbeknownst to me) drowning in wine started regularly surfacing. Most prominently a feeling of abundant joy began welling up in my chest rather unexpectedly and with frequency. A lot of water metaphors here—”my cup runneth over” with water metaphors. After some time this feeling didn’t return; suppose my system established a new baseline. But I thought it worth mentioning just thinking how rare joy must be for so many of us. And to report that I felt it briefly.

This exhibition isn’t named for that joy, though. The titled is borrowed from Stephen Kaltenbach’s painting of the same name. Despite having appeared on every relevant list of the time, Kaltenbach, a self-described “secretive person,” is perhaps the least well-known of the first-wave American “concept art” cohort. He has a number of references in Lucy Lippard’s “Six Years”; he was included in pioneering curator Harald Szeemann’s landmark exhibition “Live in Your Head: When Attitudes Become Form”; you get the picture. He emerged in New York City at the end of the 60’s, attracting attention with conceptual pieces that, with a simple phrase, injected an uncanny in the everyday and a slippage in the logic of time and space, in a manner typical of the conceptual canon. “Joy” is an instance of his “Nuclear Project,” in which he made various artistic proposals for the disposal of the world’s nuclear arsenal; in this case launching every nuke simultaneously into space, thereby creating a typographical explosion of the word in the night sky.

By 1969, Kaltenbach had a solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum, and in 1970 suddenly announced his departure from the cosmopolitan art world of New York and from the concept art practice that won him fame. In a seemingly dramatic shift, he relocated to Sacramento, California, and rededicated himself to creating meticulously detailed, large-scale psychedelic paintings.

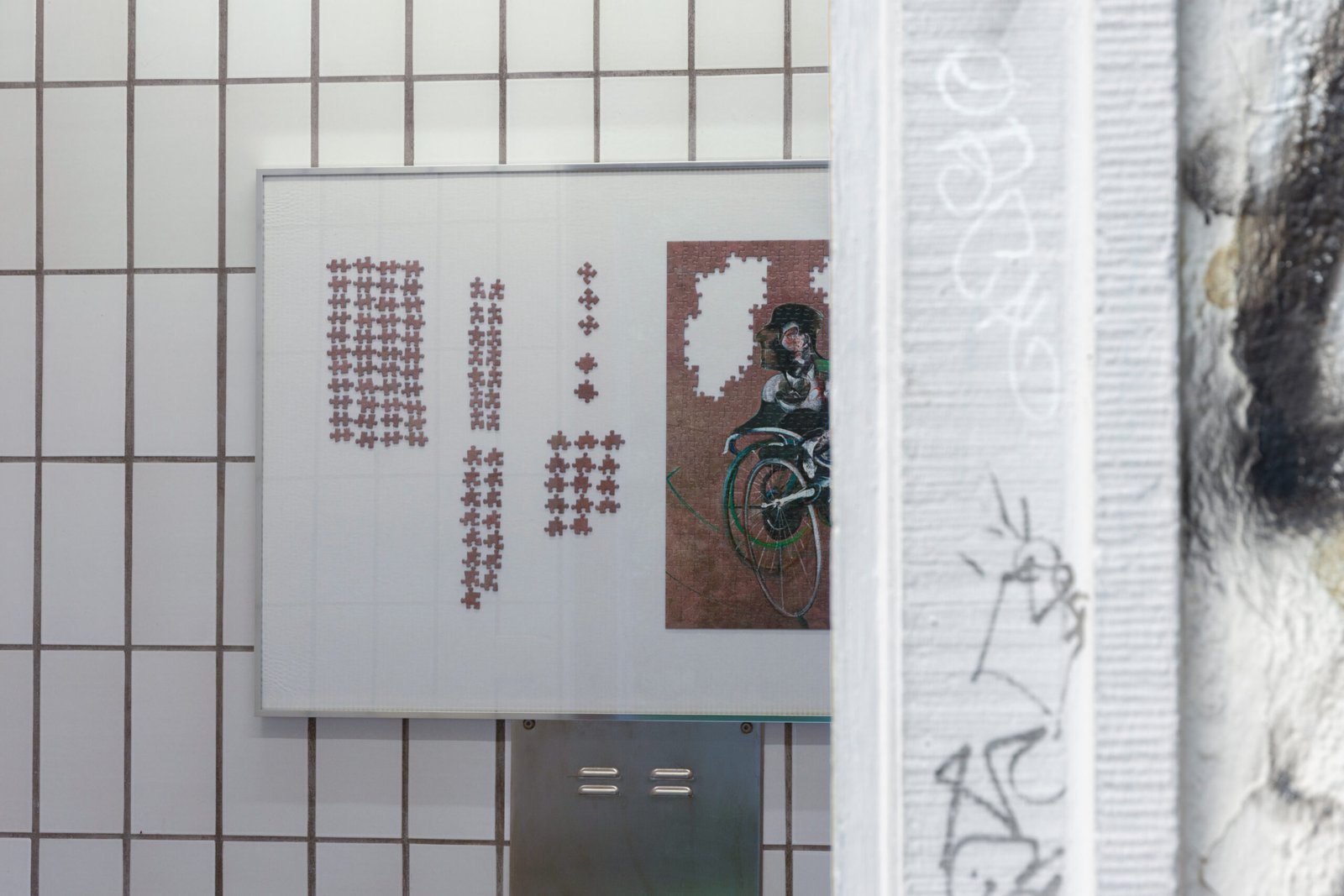

Sibylle and I found this jigsaw puzzle of a Francis Bacon painting at some thrift shop in Basel. It seems someone had bought it at the Fondation Beyeler gift shop but never bothered to open it, and an unopened thrift store jigsaw puzzle is the best kind. We assembled it on the coffee table over several days, starting with the border, then the figure. Once those had been completed we set in on the background. This part was a struggle; we even organized the remaining pieces by shape to help us place them. And after some hours of painstaking assembly, it was abandoned.

Michael Ray-Von

_______________________________________

Hunger for Joy

Yesterday I skipped lunch and proceeded alone to Fondation Beyeler to see a show I was only half-interested in. I had felt the need to look at art in person again, after having spent too much time in the comforts of digital exhibition viewing. Admittedly, I like to dwell in the conventions of institutional art viewing, and to find myself among a herd of tourists has a strangely therapeutic quality. Perhaps this intermingling with non-locals, visitors of the arts (forgive me if that sounds pretentious), allows me to let my guard down, to loosen those pretensions and usual mental routines when engaging with art. This environment allows me to lose myself in the crowd, drift through the galleries, and, above all, be physically present if nothing else.

That day the foundation was especially busy for some reason. Strutting through the galleries, pacing toward and away from paintings in a rather rhythmic manner, the succession of works seemed to grow duller and duller. My last reserves of interest were depleting as I entered the final stretch of the parcours. With my hands clasped behind my back, my eyes caught a work hanging in a noticeably darker corner of the space, as if deliberately underlit. Green, purple, yellow, and brownish brushstrokes—seemingly applied quickly and with ease—came together to depict a forest, half of it cut down to stumps. I disliked what I saw: its gestural style, its dark palette, its warped perspective. As I was about to move on, I felt my rhythm interrupted; the fleetness the work had engendered in me, the urge to move on quickly, made me stop in my tracks. I felt the need to correct myself. Looking closer at my reaction, I recognized a hasty conflation of dislike with indifference. On the sliding scale from casual disinterest to vigorous detest, my feeling landed far closer to the first pole. Sometimes we misread ourselves, I thought. Disregard wasn’t the result of the encounter itself but rather a residue of viewer’s fatigue (and, perhaps, physical hunger). In truth, I wasn’t as invested in this disregard as I had unconsciously assumed.

I decided to challenge myself and remain in front of this painting longer than any other frame in the show. At that moment, some distant fragment surfaced from the back of my mind. I don’t recall where I first heard it, and I couldn’t subsequently verify that the practice was real. But supposedly there once existed this specific method to make children remember important lessons. My memory whispers that it stemmed from some old Nordic tradition: parents would take their children to a lake, deliver a short lecture (perhaps a warning like never approach a horse from behind, or maybe a religious tenet—I concede I’m blanking on this part) and then, right after, throw the children into the water. The bodily shock of the cold, combined with the struggle to stay afloat, was said to activate survival instincts including heightened awareness and acute memory. The idea was that the just-given lesson would carve itself deeply into the child’s mind via trauma.

It does sound abusive, admittedly—but again, I’m not even sure if it’s real. What kind of lesson would warrant this absurd cruelty? Still, as I stood in front of that wonky forest painting, I imagined myself being shoved from a pier into icy water. I needed some kind of jolt, a kickstart to engage with what otherwise seemed to elude my capacity for attention. I stared through the picture and wondered: could one write a practical guide for transforming indifference towards a work of art? And I don’t mean by accessing external knowledge, by digging up an anecdote or historical tidbit pertaining to it, but through sheer mental and emotional self-determination? Through a method related to being cast into a lake, shocking the senses awake and igniting excitement in what is in front of you. I was trying to concoct a word for this procedure and came up with self-exaltation, which admittedly sounds rather close to self-pleasure—and what I was imagining, though not that, must have some relation to it as well. What other term might fit? Auto-suggestion perhaps; self-administered changes in one’s perception or brain state. I suppose the core technique would rely not just on thinking differently about the work but on acting differently towards it. I improvised a kind of guide for how to induce self-exaltation. It hinges on a certain openness, the distaste being a habitual reflex, not a conviction.

0. Have you ever tasted a lemon? A perfectly normal yellow one with its glossy, smooth peel. Imagine holding it in your hand. Smell it, take a big whiff of its fresh aroma. Now imagine moving it even closer to your nose, to your mouth and biting into it. You feel your teeth slicing through the fragrant outer layer into its juicy flesh. The acidic juice wets your lips and runs down your chin. Your teeth might ache later. It’s pretty sour, right? Can you imagine biting into it? I’m sure you can. You can taste it, no? Your mouth is producing saliva, maybe your face even twists to accommodate the shocking overload of sourness. At the back of your mouth, there’s that peculiar sensation, something like a cold shiver down the tongue. Sensory overload, and yet there’s no actual lemon. Did this description suffice to induce the taste? Are you salivating? In essence: your brain doesn’t always clearly distinguish between a real stimulus and a vividly imagined one.

1. The goal is to emulate amusement, appreciation, perhaps even reverence for the work. Take three short, deliberate inhales, stacking the breath in your chest, followed by one long, steady exhale. Repeat this sequence a few times until you feel relaxation setting in. With each cycle, allow your shoulders to drop and your gaze to soften. You might notice your awareness becoming sharper.

2. Encounter the work with a smile. If laughter arises, let it. Open your eyes wide. Look at the work as if it were the very first image you had ever seen. Notice what stirs in that fresh encounter: a patch of color, the way a line bends, a figure in the background. Don’t search for it, simply go with the flow, without questioning your impulses.

3. Give that sensation time to ripple through you. Let this connection spread outward from the fragment you chose until the whole work resonates in that feeling.

4. Walk away from the work, take a quick lap, then return with fresh eyes. Be surprised—as if you’ve never seen it before. Block the thoughts that tell you otherwise by stepping so close to the work that the alarm goes off or a guard panics and grabs your shoulder.

5. Imagine you’ve lived with this work your entire life. That it belonged to your grandmother. That it hung above your childhood bed. That it changed your life. Be specific in your tale.

6. Take a deep breath and let your gaze settle once more on the work. Now, imagine what you would say to another person about why this piece moves you and why they should care about it. Text a paragraph to a friend, or even stop another visitor in the museum to share your esteem. Again, be specific: what might attract someone to it?

7. Picture leaving the space and never seeing the work again. Imagine what this hole might feel like. Let your body convince your mind. At some point in this process, you’ll feel something shift in your attitude towards the work in question, it will speak to you. Congratulations. Even if the path toward it is winding, the performance, i.e. the rehearsal of exaltation, will turn real.

What’s the difference, after all, between pretending to like something and actually liking it? Haven’t you, at some point, convinced yourself you liked something simply because your friends liked it, the stakes were low, and it was easier not to disagree? And yet, over time, you actually began to like it. If the feeling of joy is indistinguishable, does it matter whether it arrived through self-exaltation or through “genuine” attraction? That’s the theory, at least. In my case, drafting this guide paradoxically deterred me from testing it in practice, and I left the foundation after my thought experiment had concluded successfully, even if my actual feeling toward the painting remained very much in the familiar realm of disinterest.

Later that evening, I stumbled across a video clip of a celebrity describing their cigarette addiction and claiming to have quit for over a decade after reading a particular self-help book. The Easy Way to Stop Smoking by Allen Carr promises that by the time you finish reading, you will have stopped smoking. It sounds like snake oil, yet what’s more astonishing is that Carr’s promises did not end with smoking cessation. The odd success of this book from the 1980s gave rise to a whole series of spin-offs: “Easyweigh to Lose Weight,” “The Easy Way to Stop Gambling,” and “Quit Drinking Without Willpower”—each stamped with the prefix “Allen Carr’s,” a seal of approval with registered rights.

Carr’s Easyway® method insists that tobacco dependency, food addiction, alcoholism, and the like are primarily mental addictions. From books developed seminars, that promise the same success for customers. Whatever the books’ and the seminars’ method amounts to is hard to say. (Mind you, a placebo effect, simply indicates a mechanism the current concepts of the medical field cannot yet account for.) How does Carr explain it? The company’s website assures us of its humble means:

There are no scare tactics, no horrible pictures, no substitutes, pills, lasers, or gimmicks. It’s not hypnosis, mind over matter, or positive thinking, and we won’t bang on about why you shouldn’t do it (which you already know).

Instead, we’ll focus on why you continue to smoke, vape, or drink alcohol despite knowing the obvious disadvantages.

Allen Carr’s method will question and challenge what you think you know or believe about it.

The surprising thing is that clinical studies on its effectiveness show Carr’s method to be more promising than other behavioral and pharmacological treatments. A meta-study concludes: The AC seminar may be an effective intervention for smoking cessation. This approach deserves further randomized controlled trials with larger sample sizes. Even more surprising, most German health insurance companies will cover the cost of Carr’s seminar.

I remain skeptical. After reading the first twenty pages available online, I still wonder what the underlying mechanism actually is. Admittedly, Carr’s extremely accessible, entertaining style—directly addressing the reader—does have a kind of hypnotic pull, though he insists that is not the method. (On Amazon, the book is nevertheless listed under “Hypnosis.”) In the sample I read, the shtick seems to consist largely of personal anecdotes about smoking, not always in a negative light, combined with a repeated assertion that after reading, you will, without question, decide to quit. At the same time, Carr repeatedly insists that his method is not what you think it is. Then again, the book is 288 pages long, and I only had access to the introduction. Since I do not intend to purchase it, I will avoid making claims to the nature of the method.

Ilja Zaharov