Dakota Higgins

“Apostrophe”

April 26 – June 7, 2025

Dakota Higgins’ debut solo exhibition, Apostrophe, positions the viewer within a collapsed theater of masculine power, familial nostalgia, and political spectacle. Named after the punctuation mark that denotes possession, absence, and address, Apostrophe interrogates the rhetorical and visual mechanics of authority and representation.

At the center of the exhibition are “Dentless Portraits,” a suite of presidential likenesses rendered in meticulous fidelity to their official referents — every gesture, backdrop, and artist’s signature preserved. And yet, each portrait is empty. The presidents are gone, but their seats remain, sometimes precariously upright, sometimes off to the corner, but always rendered in glitter, a material so overdetermined in its symbolism that it becomes the ideal contranym, suggesting at once opulence and detritus, celebration and degradation, sparkle and shame.

In these portraits, masculinity sits in drag. Glitter here doesn’t feminize; it exposes. It clings to structures of entitlement with a petulant joy, simultaneously monumentalizing and undermining. There is a vacancy at the heart of these images — chairs meant for presiding figures become placeholders for a disappearing act, where power is both acutely present and glaringly absent.

The word “president” — from the Latin praesidere, “to sit before” — has echoes within the familial: the patriarch at the head of the table, of the country, of the portrait. Dakota’s work collapses domestic and political staging. The family living room and the Oval Office share a flattened visual language — both are curated sets, both are backdrops for performances of control and cohesion. In his installation “Happy Place,” Dakota leans into this convergence, drawing from the iconography of the American holiday season — that idealized moment when families gather around craft tables and fireplaces, producing and consuming together. The parable of warmth becomes a mirror for the myth of leadership.

In Dakota’s work, gestures of the arts and crafts function not just as material choices, but as biographical markers. They trace back to the artist’s earliest encounters with making: surrounded by ritual and the shared labor of ornamentation. The viewer is invited to consider the act of making as one entwined with care and with compliance. In this context, the handmade ornament and the symbols of state share a genealogy. Both are made to signify belonging, to instil belief, and to perform stability, even as they conceal the fragility underneath.

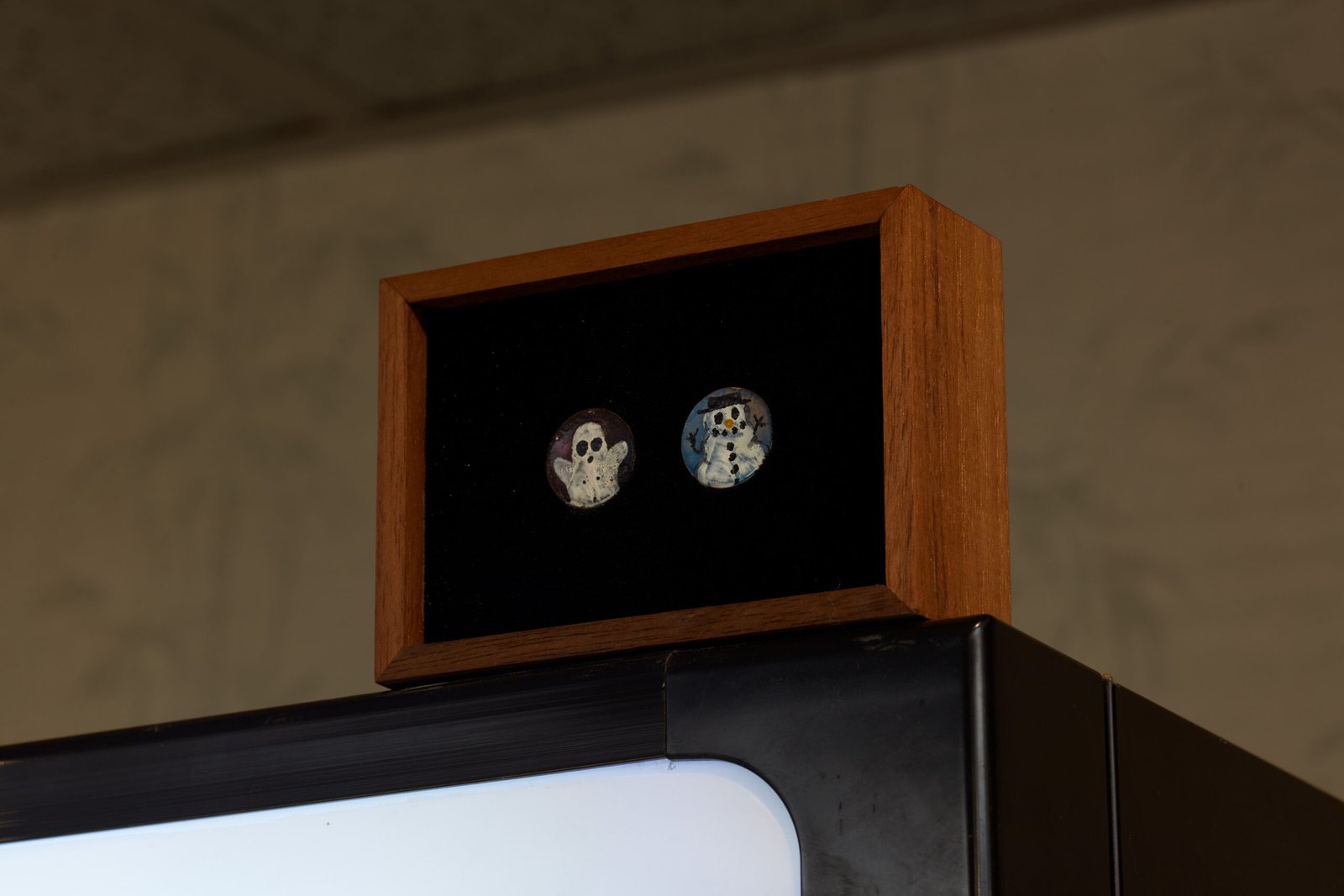

Scattered within the exhibition, American coinage appears — some framed luxuriously in walnut and velvet, but most tucked discreetly into corners, under frames, or along moldings; hidden like Easter eggs. These minor apparitions hint at the people rendered invisible by the myth of the singular great man. These quiet presences mark a refusal — a refusal to perform, to participate, to become what the portrait demands.

Dakota has never met his father. In many ways, this lifelong absence animates his project. The portraits in this show are portraits of men who “preside” over everything and nothing — symbols of fatherhood as both myth and machinery. Apostrophe captures the patriarchal structure in its purest theatrical form: reverent, absurd, and hollow.

–Raghvi Bhatia

Taken from the Feeling

Someone had shouted about a shooter. I remember thinking that if it were true, there would be gunfire. There wasn’t, but I kept running anyway. There were no screams, only the rhythm of hurried footsteps—rubber soles compressed against the floor of Terminal 1, the sound clipped and repetitious. The decision to run wasn’t a conscious one. It was a kind of submission to statistical instinct.

We spilled onto the tarmac, guided not by signs or announcements but by a distributed uncertainty. A van marked with United Airlines branding stood with its doors open. We climbed inside, filling the seats. There was no driver. No one commented on this as the absence was too ambiguous to challenge.

Then the woman beside me made a phone call to her mother. She was crying. “It’s ISIS,” she said. “I knew it. I knew it.” It wasn’t what she said that stayed with me, but the certainty in her diagnosis that caused me to lose faith in the narrative of the entire ordeal.

I stepped out of the van and walked toward the tarmac’s perimeter. After bomb dogs had done their rounds, airport officials re-screened us and we all returned to our respective gates, and flights that landed prior to the event were finally allowed to deplane.

Later, images and updates circulated online. The panic, it turned out, had originated with a man who accused another man of carrying a weapon. But the accused couldn’t be located. Officially, he hadn’t existed. Still, there was a photo: the accuser wearing a blue nylon Nike jacket, black jeans, and black sneakers. He was detained, then released. No charges, no perpetrator to the extent that the accuser’s statement was difficult to charge: “I thought I saw someone with a gun.”

A week later, during my lunch break, I went to Jade Siam in Huntington Park. I’d ordered from there before but never dined in. The interior was (wonderfully) Baroque—umbrellas, faux plants, and spotlights one might see on the stage trusses of music venues were all suspended from the ceiling. The music video playing on the muted TV was Whitney Houston’s “Where Do Broken Hearts Go.”

I sat alone for most of it. The waiter who took and brought my order disappeared into the back. When I’d finished eating, I went to the restroom. On my way out, I stopped at the counter and rang the bell. The waiter returned, looking at me with confusion—as if I had offended him.

“The owner told me your meal was paid for,” he said.

“By who?” I said looking at the empty restaurant.

He pointed to a chair at the table just behind mine. “He was sitting there,” he said.

There was no one in the chair, but a jacket I hadn’t noticed before was left draped over its back: Nike blue nylon jacket.

“Where did he go? I’d like to thank him.”

“I think he went to the bathroom,” he said. “But might be in there for a while.”

The sound from the TV suddenly returned and I took that as a ‘yes.’

—Boz Deseo Garden

Bio:

Dakota Higgins is an artist, writer, and musician based in Los Angeles. He is the founder of the experimental music venue, the DMV (aka the Departure from Music Venues). Recent exhibitions include Things Done for Love at the University of California, Los Angeles, CA; Flat Mechanics, Fluid Dynamics at Deli Grocery, New York, NY; Infra-thick at Woodbury University, Burbank, CA; and Optogenetics: Controlled by Light, Room 3557, Los Angeles, CA.

Higgins has recently been rejected from the Fine Arts Work Center Artist Residency, Provincetown, MA; the Innovative Art Grant; Headlands Center Artist Residency, Sausalito, CA; and the Joshua Tree Highlands Artist Residency, Joshua Tree, CA.