“The adults want to pass the promise of the promise on to their children. That may be the children’s only sure inheritance – fantasy as the only capital assuredly passable from one contingent space to another.” – Lauren Berlant

In what would become his most notable work, Candide, Voltaire set out to demonstrate that optimism is a delusion, not a virtue. Written in 1759, the novella is a satirical tale following the travails of the ambitious Candide, a student of local philosopher Pangloss, whose assertion that all things happen for the best in the best of all possible worlds, becomes the guiding principle of Candide’s young life. The story is a polemic against the philosophical optimism of one of Voltaire’s contemporaries, Leibniz, whose tenets he considered blatantly detached from the harsh realities of life on earth. Voltaire casts Candide into a cruel world marked by endless suffering, testing the limits of his doctrine until it withers. What began as a lofty metaphysical ideal gradually unravels. Candide, a changed man, turns his back on the divine order he once devoted himself to.

Optimism is more fragile now, more ambivalent. It is a forward-looking impulse that is, as academic Lauren Berlant argued, perhaps best understood as a form of attachment to a potential future: towards a vision of what could be. Binding ourselves to these possibilities, we blindly follow their coordinates, incorporating them into ourselves, making them our utmost. These attachments sustain us, drive us, grease the gears of our desire. But Berlant warns of this vow, noting the possibility of finding oneself excessively devoted to objects, people and aspirations that hinder us, even if and especially, they once shone bright with promise. This, Berlant considered “cruel optimism:” the tendency for our desires to turn into obstacles, thwarting our capacity to flourish. It is, in an age of rampant branding, consumption, gratification and displacement, one of the defining undercurrents of contemporary life. The modern subject is required to effortlessly bend to the demands and impulses of a landscape changing faster than the speed of reaction. Yet our attachments are cumbersome, and we remain anchored, to promises and promises of promises, and the sustenance they provide.

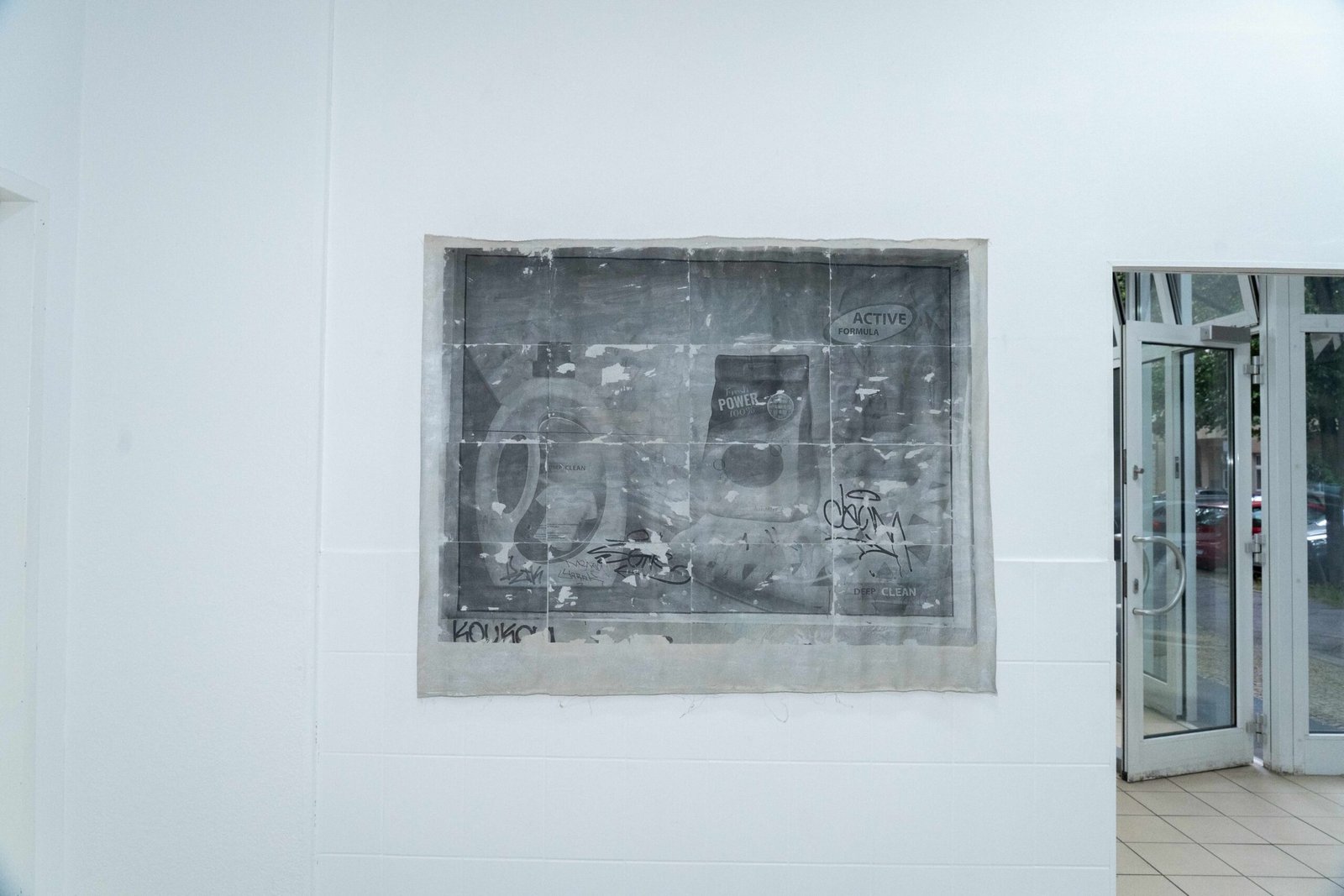

These works trace the contours of this suspended desire. They intuit the toll of waiting, the disorienting cycle of repetition, and the attachments we develop to the systems and structures we find ourselves subjected to. In this frame, divinity is fractured, scattered across our countless thoughts and gestures. The divine order of a daily commute, the divine order of intuition. Hard work, another divine order. The optimist lives under these contemporary conditions, doubtful at times, eyes on the reliable horizon ahead. If faith in tomorrow should ebb, let the residual feeling subsist. If not sincere belief, then at least the mere suggestion. Anything to kindle the flame, for it is both signal and source of warmth.

Text by Sophie Cassel & Leo Busch