Instead of looking at those who run the fastest, Helena Minginowicz looks

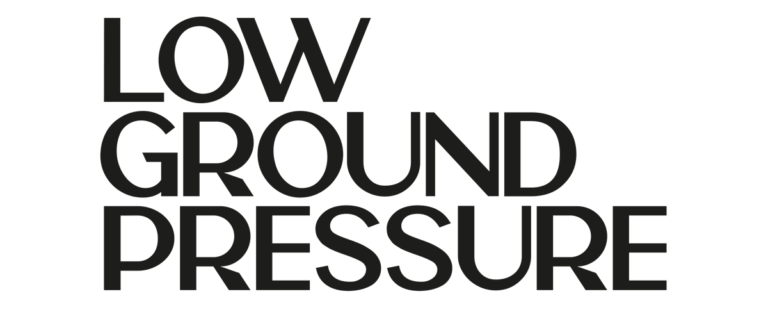

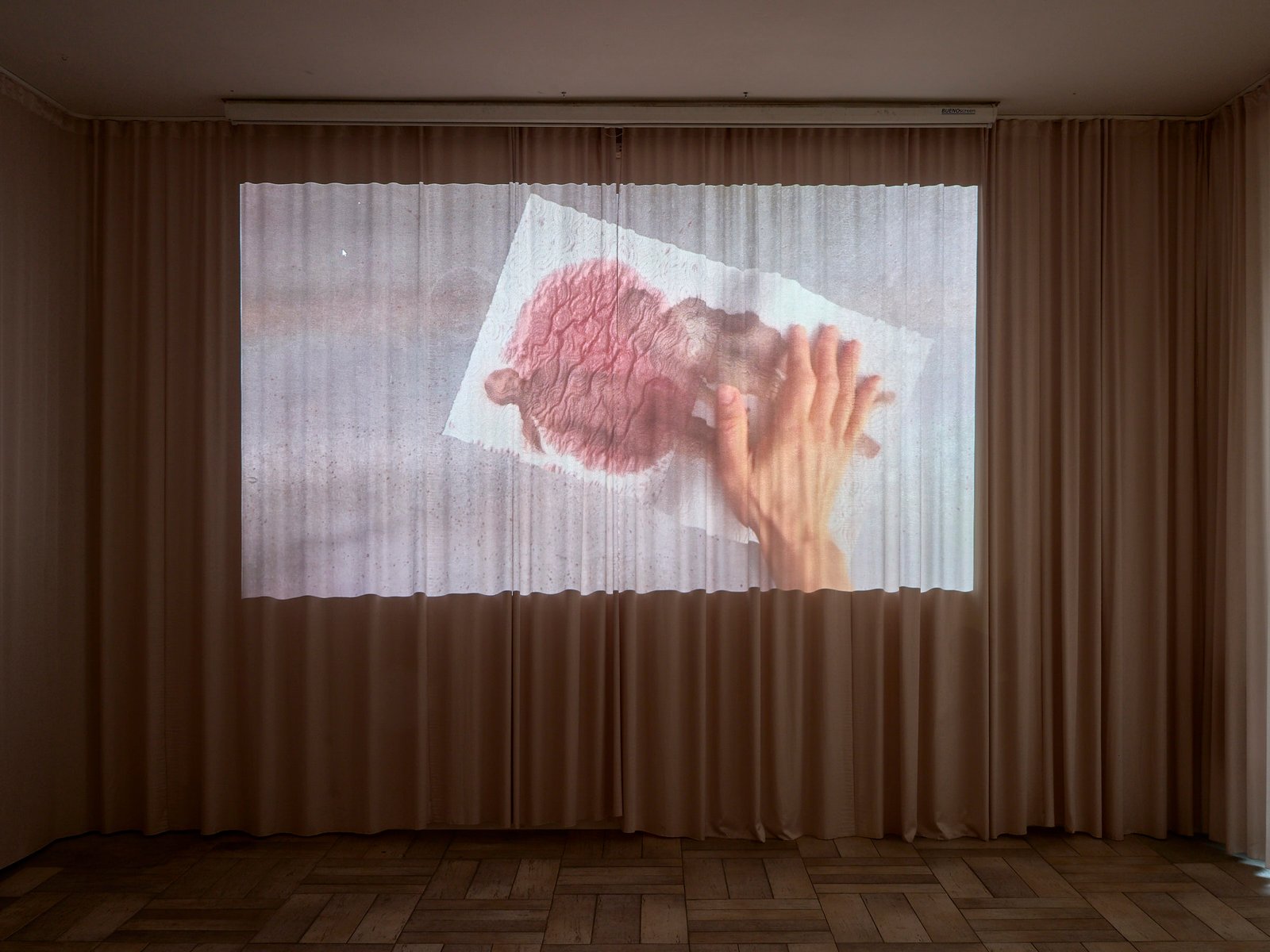

at those who had to stop. She directs her attention to fatigue, indisposition, and intimacy, which defy the formats of success. Her paintings—painted

on canvas and paper towels—record what the logic of efficiency tries to erase: slowing down, distraction, momentary vulnerability. Weakness becomes

a cognitive strategy here—it exposes our living conditions. And in the process, she criticizes a system in which strength and productivity are sold as cardinal virtues.

Minginowicz readily draws on the language of Renaissance painting—an era that, in the Western imagination, became synonymous with harmony, canon, and a belief in perfect order—only to subtly, and sometimes unceremoniously, disrupt that order. The Garden of Eden? Yes, but with

a plastic bag blown away by the wind. Venus of Urbino? Sure, but one who hasn’t yet gotten out of bed because the previous night demands a painting of its own. Van Eyck’s turban? In her version, it’s a towel that knows far too much in the morning. Here, “high” blends with “low,” and the fringe takes center stage.

At the heart of this practice is the belief that weakness can be strength.

Judith Butler would call it precariousness—a fragility shared by all, which, instead of dividing, can unite. It’s a reminder that vulnerability, the need

for care, and entanglement in relationships are not burdens, but

the foundation of community.

Ada Piekarska (curator)